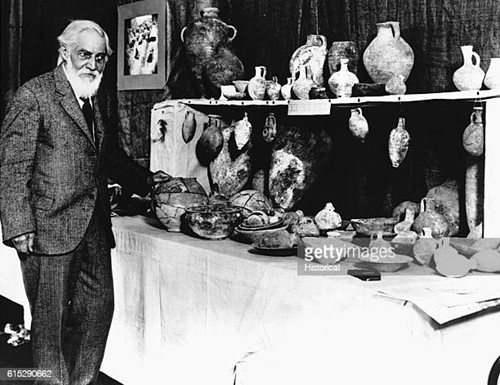

Introduction: The Father of Archaeology

Sir William Flinders Petrie, legitimately addressed as the Father of Archaeology, also was the first to systematically investigate the Pyramids in Egypt during the 1880s. He was the archaeologist whose six decades in a field produced a vast amount of archaeological evidence existed for all periods of Egyptian history from prehistoric through medieval times. Being a British archaeologist and Egyptologist who made significant impact on the techniques and methods of field excavation and exclusively developed the chronological sequence dating method that made promising the reconstruction of history from the remnants of ancient civilizations. Petrie developed his particular interest of standards of measurements, while self-studying trigonometry and geometry. Deriving from his father’s inheritance, Petrie soon developed essential skills how to use the most modern surveying equipment present at the time. Petrie roamed England gauging churches, structures, and ancient megalithic ruins, such as Stonehenge. After reading Piazzi Smyth’s Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramids, he convinced himself that he would continue his studies on Pyramids in near future.

Career as a Surveyor

After began his initial career as a practical surveyor, he was able to govern the unit of measurement used for the erection of Stonehenge, so in 1880, at the age of 24, Flinders Petrie distributed his first book entitled Stonehenge: Plans, Description, and Theories; this book would become the basis for future sightings at that site. That same year, he began his explorations and examinations of Egypt and the Middle East which lasted for more than forty years. Next 3 years (1880-1883), Petrie devoted himself to exploring, and excavating the Great Pyramid of Giza. Not surprisingly, during all these years of harsh years amidst of the constant rays of the sun, he exclusively chooses an old rock tomb as his residence and centre of all operations in Giza as well. In his own words:

“I had a doorway in the middle into my living room, a window on one side for my bedroom, and another window opposite for a store-room. I resided here for a great part of two years; and often when in draughty houses, or chilly tents, I have wished myself back in my tomb. No place is so equable in heat and cold, as a room cut out in the solid rock; it seems as good as a fire is in cold weather, and deliciously cool in the heat.”

Greatest Innovation of Field Archaeology

Petrie’s methods and design endlessly improved the practices, and hence the community vision, of archaeologists. His undeniable habit of grasping meticulous attention to detail, one of the specialties spotted during his excavations, also he studies everything unearthed. Petrie was insistent that everything excavated was to be noted, even apparently tiny innocuous items, and this was perhaps one of his most crucial contributions. They were indeed scrupulous, leading him to be known as one of the excellent pioneers of the scientific method in excavation.

In 1884 Flinders Petrie found fragments of the statue of Ramses II during their excavation of the Temple of Tanis. In 1885 and 1886, at Naukratis and Daphnae in the Nile River delta, he unearthed decorated pottery by which he demonstrated that those sites had been exchanging settlements for the archaic Greeks. It was this discovery that caused him to take into account that history could be restored through an analogy of potsherds (pottery fragments) in various stages of excavation. His first application through the principle of sequence dating has applied on the hill site of Tel Hasi, South Jerusalem, also considered as the second stratigraphic study in Archaeological research history. Most of Petrie’s equals in archaeology questioned his hypothesis that chronology could be determined by potsherds, whether painted or undecorated. But, with the gradual elegance of archaeology, the careful assessment and categorization of broken pottery became a standard technique.

In 1904 Petrie handed down the Methods and Aims in Archaeology, the final work of his time, wherein he coherently outlined the objectives and methodology of his profession alongside more pragmatic aspects of archaeology—such as details of the digging, counting the application of cameras on the field.

The thousand or so publications he produced are a witness to his relentless efforts to obtain information before it has been destroyed by modern developments over the cultivation and by urbanisation. Such output has been perhaps too fruitful in the long run, detailed and painstaking excavations which characterise archaeology in the present day, but nevertheless, Petrie’s many accomplishments had a profound influence on the subjects of Egyptology and Archaeology.