Mahinda Karunarathna, Apprentice Graduate, Regional Office, Central Province, Department of Archaeology. mahindakandy222@gmail.com – 0719945046

Dr. Mohamed Sulthan Mohamed Saleem, Senior Lecturer, Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Peradeniya. msmsaleemnadvi@gmail.com

W.M Chandrarathne, Officer in Charge & Project Manager, Maritime Archaeology Unit & Maritime Archaeology Museum, Galle project, Central Cultural Fund. chandraratne7@yahoo.com

Location

The ancient harbor Ambalangoda is located in No 85 – Patabandimulla Grama Niladari Division (GND) of Ambalangoda Secretariat Division (SD), Galle District, Southern Province (6°14’07.4″N, 80°03’03.1″E) and about 800 m along the Ambalangoda – fisheries harbor road and 200m to the North from the jetty of fisheries harbor.

[wpgmza id=”2″]

Historical background

The great Chronicles Mahavamsha and Sandesa kavviya (messenger poems) had not mentioned about the activities of the ancient harbor at Ambalangoda. Thisara Sandesaya (1344-1359 AD) (Gunawardane, 2001 p. 1), Parevi Sandesaya (After 1415 AD) have described the coastal areas of the Southern province near Ambalangoda in their poems. Kalutota, Maggona, Beruwala, Aluthgama, Kosgoda, Bentota, Welitota (Balapitiya), Madampamodara, Totagamuwa, Rathgama mentioned in Thisara and Parevi sandesyas (Jayatilake, 2002 pp. 97, 101, 102, 103, 104, 107, 108, 109, 113; Gunawardane, 2001 pp. 101, 103, 107, 108, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116). However, one notable thing is the name “Ambalangoda†has not mentioned in this Sandesas.

Portuguese, Dutch and English (1505-1948) records depict the social, political, economical, religious relationships in the Ambalangoda harbor.

Research History

Three groups of Archaeology, Maritime Archaeology, and Harbour Development Project have intervened to the Maritime Archaeological activities in the Ambalangoda Harbor from 1998 to 2012.

The Artifacts found from the investigations in the Harbour

The Artifacts found in 1998

Most of the artifacts had been found by the private persons. On 14th May 1998, a maritime archaeology team (Department of Archaeology and volunteers) had carried out a preliminary investigation in the harbor (Jayatilaka, Gihan; Nerina de Silva, 1998 p. 1; Maritime Archaeology in the Ancient harbour at Ambalangoda, 2016 p. 32). According to the eyewitnesses, the timbers lie parallel to the shore. However, the team did not unearth the position of the wreck. Most of the artifacts found from the site had sold to the local dealers. The team gathered the information about the artifacts through interviews with eyewitnesses. The locals brought out various artifacts from their house and allowed to be photographed and recorded. 21 artifacts under 8 categories (A-H) were recorded by the group (Jayatilaka, Gihan; Nerina de Silva, 1998 pp. 1-5; Maritime Archaeology in the Ancient harbour at Ambalangoda, 2016 p. 32) (Table No 1).

[wpdatatable id=1]

The Artifacts found in 2007

The Ambalangoda harbor development project was carried out in 2007. Several types of artifacts emerged while digging the sea bed of the harbor. Cowry shells (Cypraea moneta), copper plates and ceramics are some examples of the artifacts. Two Arabic inscriptions can be seen in two copper plates.

The Artifacts found in 2012

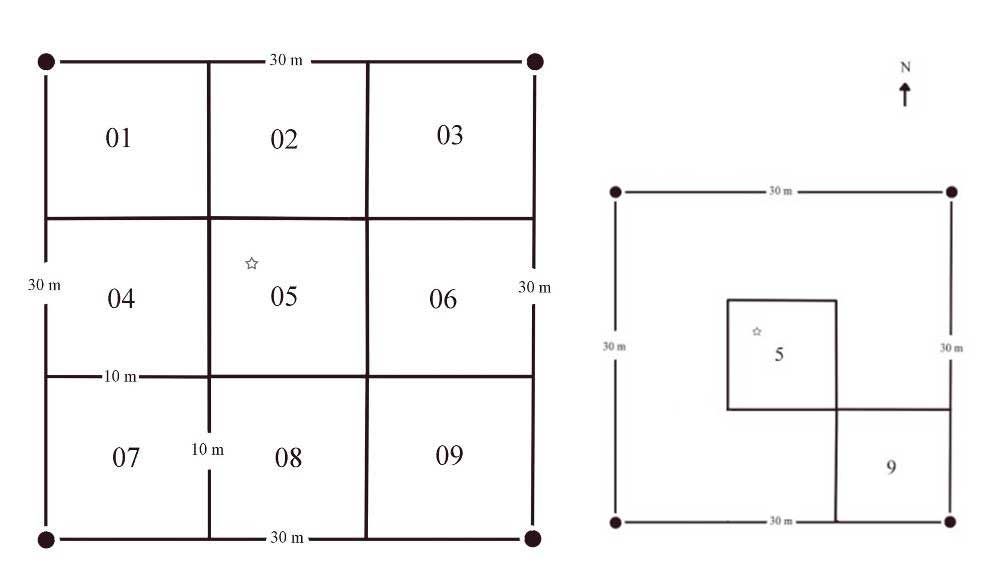

The Maritime Archaeology Unit (MAU) of the Central Cultural Fund (CCF) has explored and excavated the site (Grid No 5 & 9 / 10 m x 10 m) from 1st of March to 10th of April 2012 to unearth more archaeological objects that belong to the ship wreck. Unfortunately, the team did not find any object from the site (Ambalangoda Exploration & Excavation Report – 2012, 2012 p. 5).

(Ambalangoda Exploration & Excavation Report – 2012, 2012 pp. 10-11 ).

The Arabic Epigraphy found from the Harbour at Ambalangoda

Introduction – The Ambalangoda harbor development project was carried out in 2007 while digging the sea bed unearthed several types of artifacts. Discovering 5 copper alloy plates were a remarkable finding of the site(Table No 2). A notable thing whichcan be seen is two epigraphy in the reverse of the copper plates number 2 (2007/SL/S/AMBA/02 ) and 5 (2007/SL/S/AMBA/05).

[wpdatatable id=2]

The above table shows five copper alloy plates which have been displayed in the Maritime Archaeology Museum (MAM) of Central Cultural Fund in Galle Fort.

Epigraphy on copper alloy plates

I. Description of the epigraphy

This epigraphy is very small, 71.68mm in length ,1 mm in depth of the letters and ,10. 68667 mm in Length of a letter. Thickness is 1.21 mm, Radius 29 cm, Width 14.5 and Weight 697.3 g (copper plate 2) and Thickness 0.75 mm, Weight 285.4 g (copper plate 5).

The plate has fragmented into two parts, probably, when it was under the sea bed or when digging the sea bed by the high-pressure water dredger. There are no decorations in the obverse and the reverse of the plate. The five plates have been made of copper alloy. This plate with epigraphy was deteriorated. It is covered by the brownish or blackish “patinaâ€. This plates were conserved in 2014 before being displayed in the Maritime Archaeology Museum in Galle.

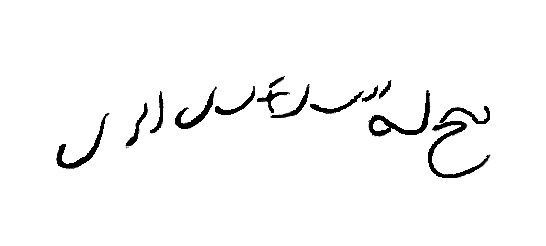

II. Photographs and stamp pages of the epigraphy

Epigraphy 1

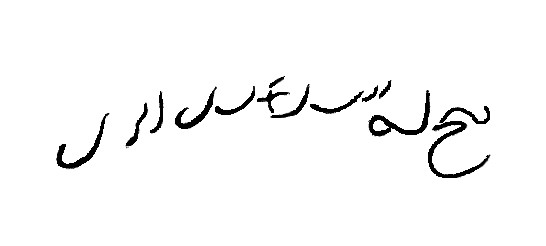

Epigraphy II

III. Translation of the Two Arabic Epigraphs

The period between the fourth and sixth centuries A.D. is generally considered to be a period of decline for the trade of Arabia.

The Arabic alphabet has 28 letters, all representing consonants, and is written from right to left. Twenty-two of the letters are those of the Semitic alphabet from which it descended, modified only in letters form, and the remaining six letters represent sounds not used in the languages written in the earlier alphabet.

It is a Southern Central Semitic language spoken in a large area including North Africa, most of the Arabian Peninsula and other parts of the Middle East.

Arabic is a language of the Quran and is the religious language of all Muslims. Literary Arabic usually called Classical Arabic, is essentially the form of the language found in the Quran, with some modifications necessary for its use in modern times; it is uniform throughout the Arab world. Colloquial Arabic includes numerous spoken dialects, some of which are mutually unintelligible (The New Encyclopedia Britannica,vol:1,, page: 508, 509, 51015th Edition, 2005, U.S.A).

Ceylon was earlier known to the Arabs on account of its pearl-fisheries and trade in precious stones and spices, and Arab merchants had formed commercial establishments there centuries before the rise of Islam (Abid;Page 838). This Arabic letter had been written without dottings, it reveals the early era before Islam, because after introducing Islam ,dotting to Arabic was introduced to make it easy to recite the Holy Quran.

Translation of the Epigraphy

Epigraphy 1

Arabic (Ù…Ù†Ø Ù„Ù‡ سيد عبد الرب) / (Manehe Lahu Sayyid Abdul Rabb)

English “Mr. Abdul Rabb Awarded to himâ€

Epigraphy 2

Arabic (Ù…Ù†Ø Ù„Ù‡ سيد عبد الرب) / (Manehe Lahu Sayyid Abdul Rabb)

English “Mr. Abdul Rabb Awarded to himâ€

This first epigraphy similar to the second epigraphy

Here this Arabic letter was written without dotting, its meaning is: “Mr. Abdul Rabb Awarded to himâ€, (Ù…Ù†Ø Ù„Ù‡ سيد عبد الرب), (Manehe Lahu Sayyid Abdul Rabb), Early Arabic writing had been included without dots. The dots found today in Arabic writing were one of the first innovations that came after the spread of Islam. These dots make it clear what consonant is to be pronounced. Before the dots, people read the text without any dots. They could do this through their experience. Arabic Writing has been using dots since the dotting system was first inventedby Abu al-Aswad Al-Du’ali ( 603–688 A.D) to prevent grammatical errors. He was a close companion of fourth Khaliphat Ali bin Abi Talib and grammarian. He was the first to place dots on Arabic letters and the first to write on Arabic linguistics.

Acknowledgment

Director-General, Department of Archaeology, Director General, Central Cultural Fund, Mr. Rasika Mutukumarana, Maritime Archaeology Team of the MAU, Mr. Chandima Ambanwala, Miss. Mangali Dissanayake and Mr. Saman of Maritime Archaeology Museum, Mr.Sumeda Weerawardana, University of Peradeniya.

References

- Ambalangoda Exploration & Excavation Report – 2012, Maritime Archaeology Unit, Galle, Unpublished, 2012.

- Gunawardane, A.D.S. 2001. Tisara Sandesaya. Colombo 10 : Samayawadana, 2001.

- Jayatilake, K. 2002. Wimarshana Sahitha Parevi Sandesaya. Gangodawila : Pradeepa publishers, 2002.

- Jayatilaka, Gihan; Nerina de Silva. 1998. Ambalangoda Shipwreck Report on a Prelminarii Investigation. s.l. : Unpublished , 1998.

- Maritime Archaeology in Ancient harbour at Ambalangoda. Karunarathna, Mahinda; W.M Chandrarathne. 2016. Colombo 7 : Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka, 2016.

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2005, vol:1,, page: 508, 509, 51015th Edition, 2005, U.S.A.