By Somasiri Devendra and Prof. Sarath Edirisinghe

Questions, and an Answer

Like so many good things, what follows is a spin-off ┬áfrom the ÔÇ£CeylankanÔÇØ.

Last year Devendra wrote to the Editor of the ÔÇ£Sunday TimesÔÇØ voicing a question that had vexed him for long, and the Editor was kind enough to carry my query, as follows:

ÔÇ£On re-reading Andrew ScottÔÇÖs piece on the ÔÇÿCapture and exile of the last king of KandyÔÇÖ in the ISLAND of February 4th, 2013, I was struck by a small but important fact. He quotes DÔÇÖOyly on the capture of the king thus:

“This morning the king again desired to see me and formally presented to me his mother and his four queens, and successively placing their hands in mine, committed them to my charge and protection. These female relatives, who have no participation in his crimes, are certainly deserving of our commiseration in his and particularly the aged mother who appears inconsolable, and I hear has been almost constantly in tears since the captivity of her sonÔǪÔÇØ

Note the references to the KingÔÇÖs aged mother, which I have emphasized. Later, Andrew Scott quotes Henry Marshall about the embarkation of the Royal party:

ÔÇ£The king embarked, with his wives and mother-in-law, in the captain’s bargeÔǪÔÇØ

Here there is no reference to an ÔÇ£aged motherÔÇØ, but a ÔÇ£mother-in-lawÔÇØ appears on stage. Is this an error ÔÇô or not? If not, what really happened to the KingÔÇÖs mother? Was DÔÇÖOyly mistaken and that she was not the ÔÇ£motherÔÇØ but the ÔÇ£mother-in-lawÔÇØ? If not, she was not in the KingÔÇÖs party: what records do we have of her after the KingÔÇÖs departure? The answer to this conundrum comes to us from ÔÇô of all places! ÔÇô Australia.

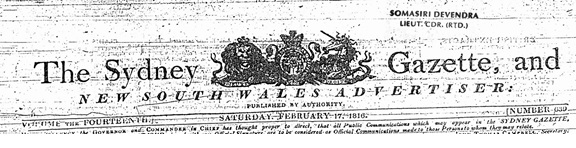

Sometime ago, some members of the Ceylon Society of Australia were investigating the story of the first person from Ceylon to have been banished to the penal colony of Australia. As the story has been published both in Sri Lanka and Australia, I shall not repeat it here, other than to say that a genealogical search in Australia by a descendant, Glynnis Ferguson, for the founder of the OÔÇÖDeane family there. [ see also M.D.(Tony) SaldinÔÇÖs ÔÇ£Banishment of the first Sri Lankan family to AustraliaÔÇØ in the SUNDAY ISLAND of 12th. January, 2003] ┬áAmong the first-hand material found was a newspaper: ÔÇ£The Sydney Gazette, and New South Wales AdvertiserÔÇØ, Volume the Fourteenth, dated Saturday, February, 1816

The paper announces the arrival of, and the ÔÇÿhuman cargoÔÇÖ, aboard the ship Kangaroo, from Colombo. Quite some space is devoted to a description of the ÔÇÿMalayanÔÇÖ prisoner from Ceylon his wife and children, and the tone is one of great sympathy. But one little paragraph, apparently reporting something the Captain said, caught my eye:

ÔÇ£The reduced King of Kandy, who is a native of the Malabar Coast, is held close-prisoner at Colombo, – His mother died there during the stay of the Kangaroo, and was interred with royal honours.ÔÇØ (Emphasis mine)

So the old Queen Mother died before she saw her son deported. But where was she interred with royal honours? Whether she was interred according to Buddhist or Hindu rites, she must have been cremated: but where? And where were her ashes interred ÔÇÿwith royal honoursÔÇÖ? What information could we hope to find about her death, the honours accorded and the place she was interred?

In fact, what do we know about her, at all?

After all, she was the mother of our last King, and we should, surely, accord her our own (Republican, not Royal) honours? Being unable to undertake this search myself, may I ask that a historian or archivist to flesh out this story?ÔÇØ

No answers were forthcoming but, serendipitously, Prof. Edirisinghe [of the Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University] did have some, and he forwarded them to the ÔÇ£Sunday TimesÔÇØ. He awaited the publication but, alas!, the Editor did not deign to publish it. After a while, Prof. Ediriweera agreed to the publication of his answers to the questions raised, as Devendra felt it too good to languish unread.

ÔÇ£Buried with Royal Honours in Vellore; last days of Sri VikramaÔÇÖs mother.

A short article, under the caption, Buried with Royal Honours and Forgotten appeared in the ÔÇÿPlusÔÇÖ section of ÔÇÿThe Sunday TimesÔÇÖ (2nd June 2013, written by Somasiri Devendra. He invited the readers to ÔÇÿflesh outÔÇÖ the story of the burial of the mother of Sri Vikrama Rajasimha, the last King of the Kandyan kingdom. The question or the confusion was regarding a statement made by DÔÇÖOyly and a news item that appeared in The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. The central character in the story is the mother or the mother in law of the deposed king.

As emphasized by Mr. Devendra, DÔÇÖOyly clearly says that the morning following the capture, the king desired to meet him. At the meeting that followed, the king presented his four queens and the mother to DÔÇÖOyly. According to DÔÇÖOyly the King had been reserved at first and on being assured that they would be treated kindly, betrayed evident signs of emotions and taking the hands of his aged mother and his four wives presented them to him one by one and ÔÇÿrecommended them in the most solemn and affecting manner to his protectionÔÇÖ. The confusion arose because Henry Marshall in his book ÔÇÿCeylon, A general Description of the Island and Its InhabitantsÔÇÖ says about the deportation of the ex-king that the deposed king embarked, with his wives and mother in law in the captainÔÇÖs barge and the attendants in another. Mr. Devendra states that, sometime ago, the ÔÇÿCeylon Society of AustraliaÔÇÖ was investigating the story of the first person from Ceylon who was banished to the penal colony of Australia and one of the first hand material found was the news paper ÔÇÿ The Sydney gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (Volume 14, Saturday February 1818). The paper had announced the arrival of a human cargo on board the ship Kangaroo from Colombo. Apart from the story of OÔÇÖDeane and his Kandyan wife and children, the first family to be banished from Ceylon, the captain had also stated that, ÔÇÿÔǪ..The reduced king of Kandy, who is a relative of the Malabar Coast, is held close prisoner at ColomboÔÇØ. The captain goes on to say that the kingÔÇÖs mother died while the Kangaroo was in the Colombo harbor and was interred with Royal honours. What Mr. Devendra requested was information on where the burial or the cremation took place and the honours accorded to mother of the deposed king.

Sri VikramaÔÇÖs (formerly Konnusamy Naik) mother was Subbamma Nayaka and the father was Sri Venkata Perumal. Subbamma Nayaka was a sister of one of Rajhadi RajasimhaÔÇÖs queens. He was born in India in 1780 and arrived in the island of Lanka with the queens of Rajhadi Rajasimha. There are numerous stories regarding the paternity of this king, some involving the chief Adgar of the Kandyan courts. On the death of Rajhadi Rajasimha, apparently following a malignant fever, Pilimatalauve, the first Adigar put forward this eighteen year old lad with not much formal education to the vacant throne of the Kande Uda Rata. This departure from the traditional rules of succession, sidelining Queen UpendrammaÔÇÖs brother, Muttusamy was considered as a plan by the first Adigar to usurp the young king at a later date in order to place him on the Kandyan throne. The records show that the kingÔÇÖs mother was in the Kandyan courts throughout his reign that ended on the 10th of February 1815.

Sri Vikrama had four consorts ÔÇô Venkataraja Rajammal, Venkatamima, Moodoocunamma and Venkata Jammal. It was customary for a large retinue to accompany new brides to the Kandyan courts. Therefore at least two mothers in law would have been in the palace if two of the queens were sisters. At the time of deportation of the ex-king and his relatives there were two fathers in law, named in a list prepared by the British

Detailed descriptions are available regarding the capture of the fleeing King. The king had been hiding in the house of an Arachchi at Galleyhe Watta with two of his queens. They were captured on the 18th of February 1815. The king and the two queens were later united with the other queens and the kingÔÇÖs mother. The Royal family was transferred to Colombo under the protection of the British, reaching Colombo on the 6th of March 1815. The king and his immediate family lived quite comfortably in Colombo until the 24th January 1816, when he and his all relations, dependents and adherents amounting to about hundred individuals were transferred to India. Although Marshall says that the king with his queens and the mother in law embarked at Colombo on board H. M. ship Cornwallis, a detailed description of the embarkation left by E. L. Seibel (see below P. E. E. Fernando) mentions the king and his four queens embarked on the Cornwallis, but makes no reference to the mother or a mother in law of the king. Prof. Fernando in his paper says that Robert Bownrigg informed Rt. Hon. Hue Eliott, the Governor ÔÇô in- Council at Ft. St. George, Madras about the deportees and four separate lists of kingÔÇÖs relatives, classified according to the relationship to the king, were forwarded. The same paper gives the List No.1 ÔÇô Immediate family members, as a foot note which gives the names and the relationship to king of ten persons. Two of his fathers in law and an aunt are mentioned but there is no mention of either the mother or a mother in law. K. T. Rajasingham, writing in the Asia Tribune (Volume 12) says that the declaration and the parole of the prisoner of war are found in a document of eight pages carrying two sets of signatures of kingÔÇÖs adherents. The first set dated 8th March has 62 signatures (some are thumb prints) and the second dated 27th July 1816, numbering altogether 168 Nayakkars.

The exile of Sri Vikrama is detailed in British records in India. Prof. P. E. E. Fernando, one time Professor of Sinhalese at Peradeniya in his paper on the ÔÇÿDeportation of Sri Vikrama Rajasimha and his exile in IndiaÔÇÖ, published in the Ceylon University Review (volume xx, 1966) quotes the records kept by the British on the prisoner king in the Vellore Fort which proves that the kingÔÇÖs mother was still alive in the fort and details about her subsequent death. These records maintained by the British detail the administrative problems regarding non-stop harangues by the king for increased allowances, provisions, coming of age of his daughter, marriage preparations of his daughter, birth of a son, plans of the British to educate the boy and the state of health of the kingÔÇÖs mother, her death and the building of a monument. Thus it is very clear that the kingÔÇÖs mother was in fact with the family up to her demise in January 1831. There are several instances mentioned in Prof. FernandoÔÇÖs paper where the Paymaster requests sanction for various expenditure with regards to kingÔÇÖs mother.

The king became quarrelsome frequently during his days in the Vellore Fort. Once when he quarreled with his brother on law ÔÇô Coomaraswamy, the authorities decided to transfer the relative. The king intervened to say that in case his mother dies there will not be a brother in law to perform the funeral rites. At one time the Paymaster asks his superiors in Madras whether they would sanction the expenditure needed for the funeral of kingÔÇÖs mother in the event she dies. The Secretary of the Kandyan Provinces directed that the expenses for the funeral of the kingÔÇÖs mother, in the event of her death, be decided by the Paymaster in compliance with any orders the Ft. St. George might desire to give, stating that he saw no reason why a larger allowance should be given then than in the case of the funeral of the kingÔÇÖs aunt (named in the List No.1 of deportees)

As for the Royal Honours mentioned by Mr.Somasiri Devendra the following paragraph from Prof. FernandoÔÇÖs paper gives glimpse of what actually happened.

ÔÇ£In 1826 the kingÔÇÖs mother became seriously ill and the Paymaster taking timely action sought permission from authorities at Ft. St. George to employ a party of soldiers to accompany the remains of the royal lady, in the event of her death to the cemetery. The authorities in Madras had no objection to a party of native officers being employed to accompany the remains of the kingÔÇÖs mother in the event of her deathÔÇØ. A sum of Rs. 3000/- 3500 was sanctioned for the expenditure.

Towards the end of 1831 the kings mothers condition became alarming and Lt. Col. Stewart wrote as follows. It is customary with Hindoos of distinction and particularly with persons of the captives rank to preserve in tombs or transmit to Benares the bones of deceased relatives or erect over ashes a building.Brindhavanam; the latter has been the usage of the Kandyan family and .king possesses a drawing of the family tombs at Kandy (the Adhahana Maluwa). The colonel therefore suggested that a piece of land situated near the river and to the left of the road from Vellore to Chittore should be acquired for the purpose of erecting a Brindhavanam.

The kingÔÇÖs mother died in last week of January 1831. Prof. Fernando, quoting British records, says that arrangements were made for a party of fifty men, all Hindus, commanded by a native officer and a drummer and a fifer to escort the remains of the deceased lady to the place of sepulcher on the banks of the river. The escort was provided with three rounds per man of blank ammunition.

It is now clear that the lady that was buried with royal honours, as narrated by the captain of the Ship Kangaroo, was not the mother of Sri Vikrama. If an event as stated in the ÔÇÿSydney Gazette and the New South Wales AdvertiserÔÇÖ really took place in Colombo, it certainly was not concerning the kingÔÇÖs mother. The lady in question was more likely to be the mother in law of the king. She must have died soon after reaching Colombo since her name was not in the List No.1 of the deportees while the names of the two fathers in law were included. The aunt named in the list died in Vellore.ÔÇØ

The questions that had originally been posed have now been answered. It was not the old Queen Mother who died in Colombo, but a mother-in-law of the King. When the Queen Mother  died later, in Vellore, she was given the royal honours that the British considered due, and these are described in Prof. Edirisinghe.

And so the mystery is solved.

Superb research ! Historical detection at its best !

Great article !!!!