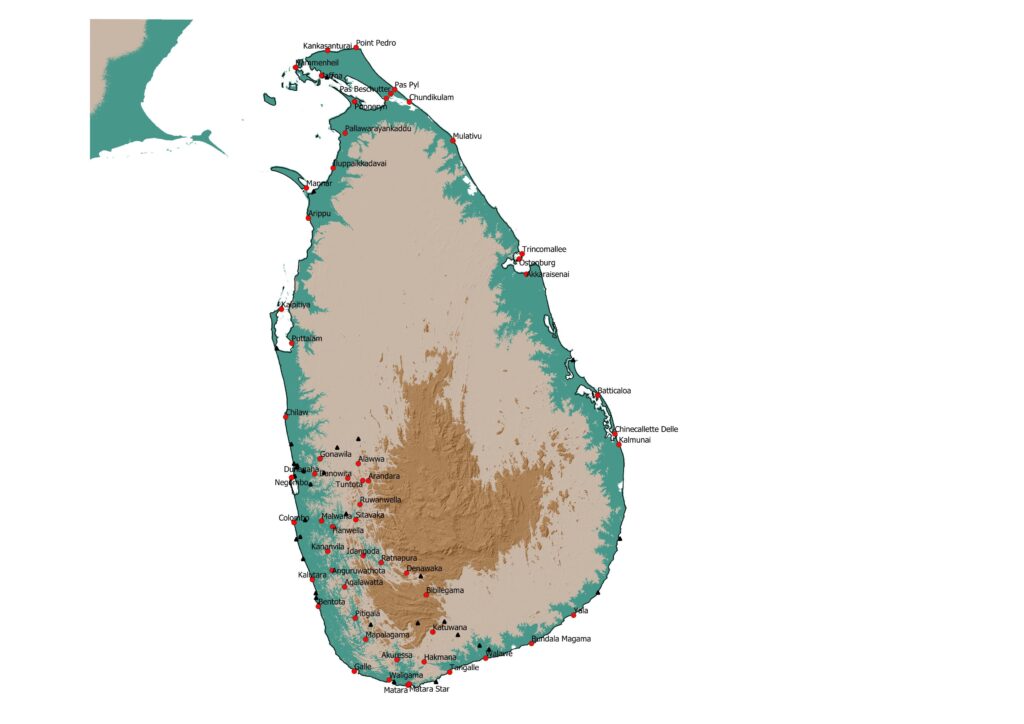

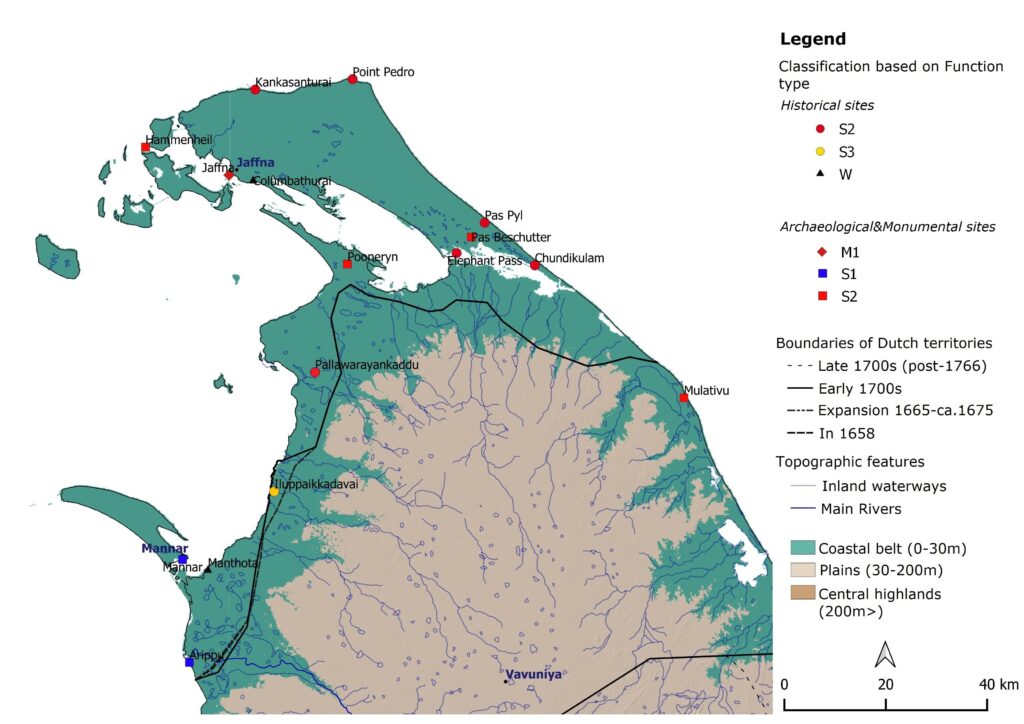

The Dutch forts of Sri Lanka are a unique group of monuments of the islandÔÇÖs tangible cultural heritage. Built by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in the 17th and 18th centuries during their occupation of the littoral, these forts ranged from large fortified towns and citadels to small forts with a garrison of just 20 soldiers. During the Dutch occupation from 1638 to 1796, they built about 60 forts and numerous other smaller fortifications right around the country with two main concentrations in the west and north of the island. Of these numerous forts, today 11 forts survive as complete monuments and about 9 in varying degrees of remains.

A. NelsonÔÇÖs The Dutch Forts of Sri Lanka (1984) was the first major work in documenting them, their conservation status, and military analysis and is thus the most well-known study specifically on Dutch fortifications of Sri Lanka. The thesis of Ranjith Jayasena ÔÇ£Om oogh in ÔÇÿt zeyl te houdenÔÇØ Historische archeologie van het VOC-grensfort Katuvana in Sri Lanka (2002), and the short paper by Ranjith Jayasena and P. Floore, Dutch Forts of Seventeenth-century Ceylon and Mauritius: An Historical Archaeological Perspective (2010) serve as the next major works in documenting the VOC forts and the formation of a typology and classification based on form and function.

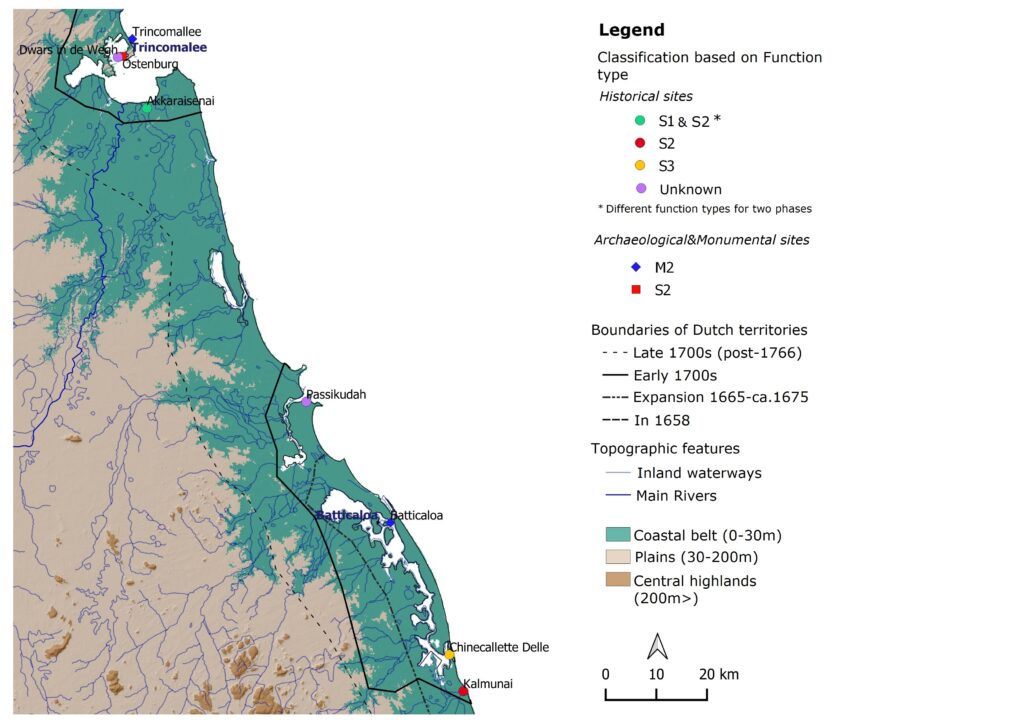

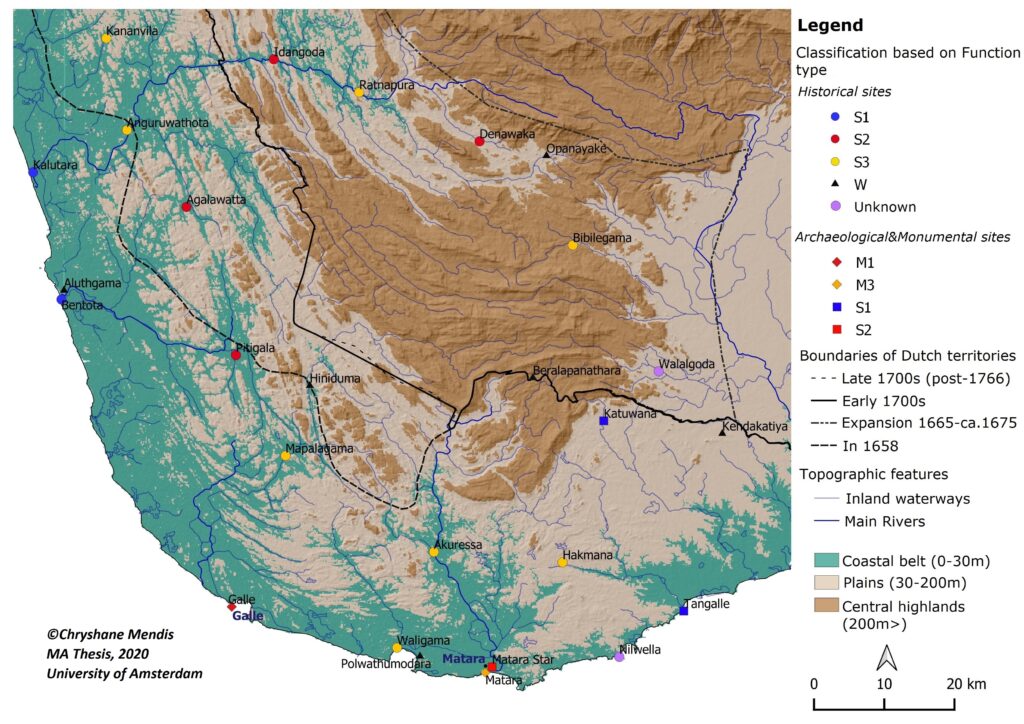

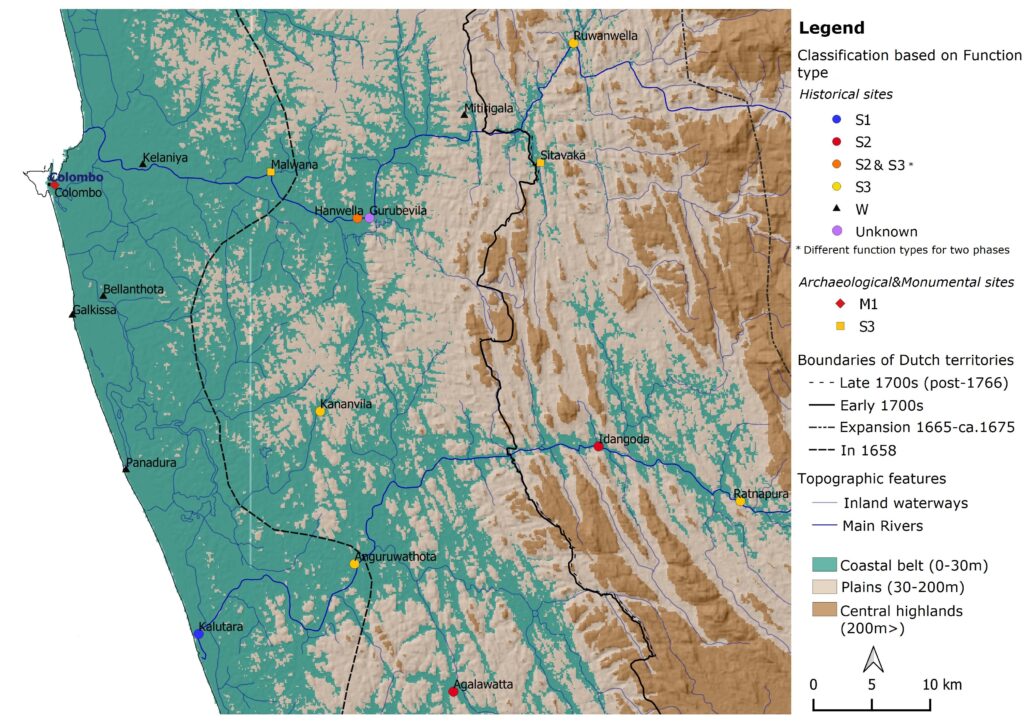

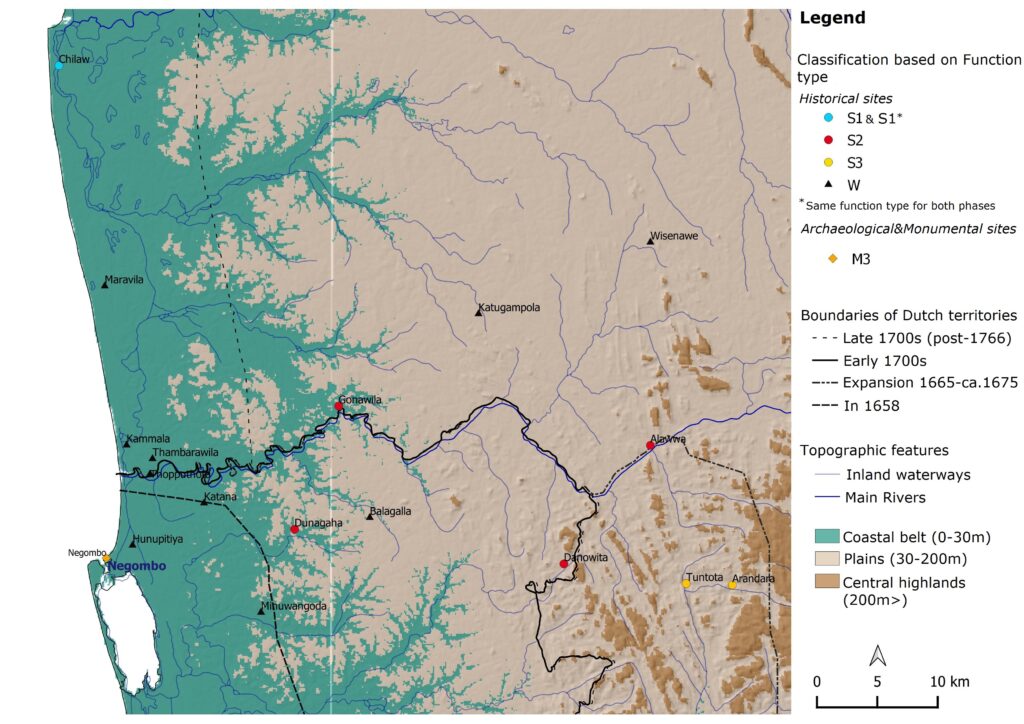

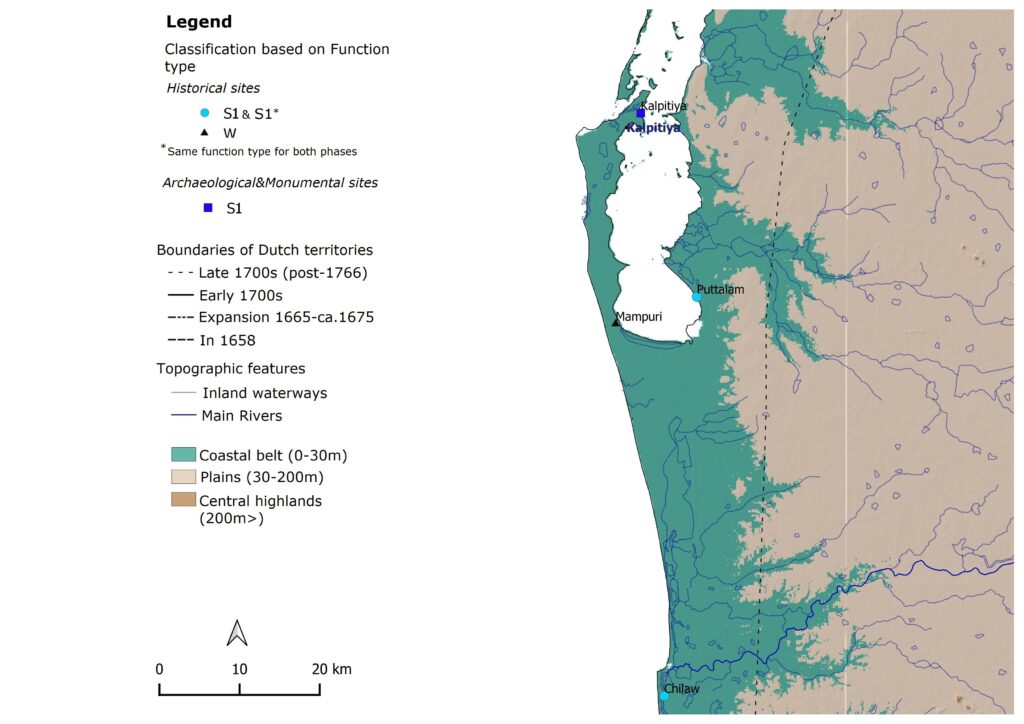

My Master’s thesis (2020) titled ÔÇ£Fortifications and the Landscape: A GIS Inventory and Mapping of Kandyan and Dutch Fortifications in Sri LankaÔÇØ from the University of Amsterdam,┬á took the work of Dr. Ranjith Jayasena a step further by building a spatial database through a Geographic Information System (GIS) which involved inventorying and mapping of these forts.

I conducted a deeper historical survey and noted down several more fortification sites not noted by the previous studies and attempted to precisely locate them. It turns out that apart from the well-known sites which survive today, there were many more forts established by the Dutch, and since much of these sites existed for only a short period of time (generally during times of war), their exact locations have been lost and are probably known only locally.

This rather extensive article serves to disseminate this knowledge to a general audience; discussing the nature of the forts, i.e., their architecture and function and their locations.

Architecture

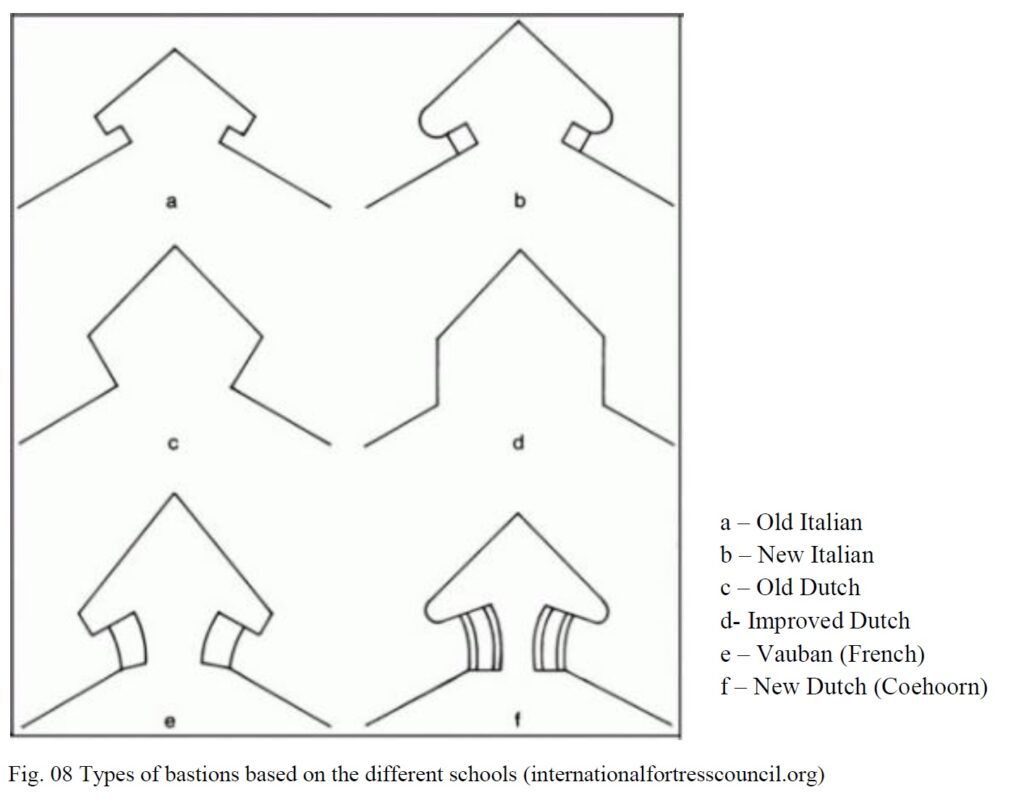

First, a brief look at the architecture of the Dutch forts. European military architecture saw a revolution with the introduction of gunpowder weaponry in the 15th century. This was pioneered by Italian engineers in the late-15th century and the key element in this new design was the bastion.[1] From the 16th century onwards military architecture became a complex field of engineering in Europe with several ÔÇÿschoolsÔÇÖ such as the Italian, Dutch and French.[2]

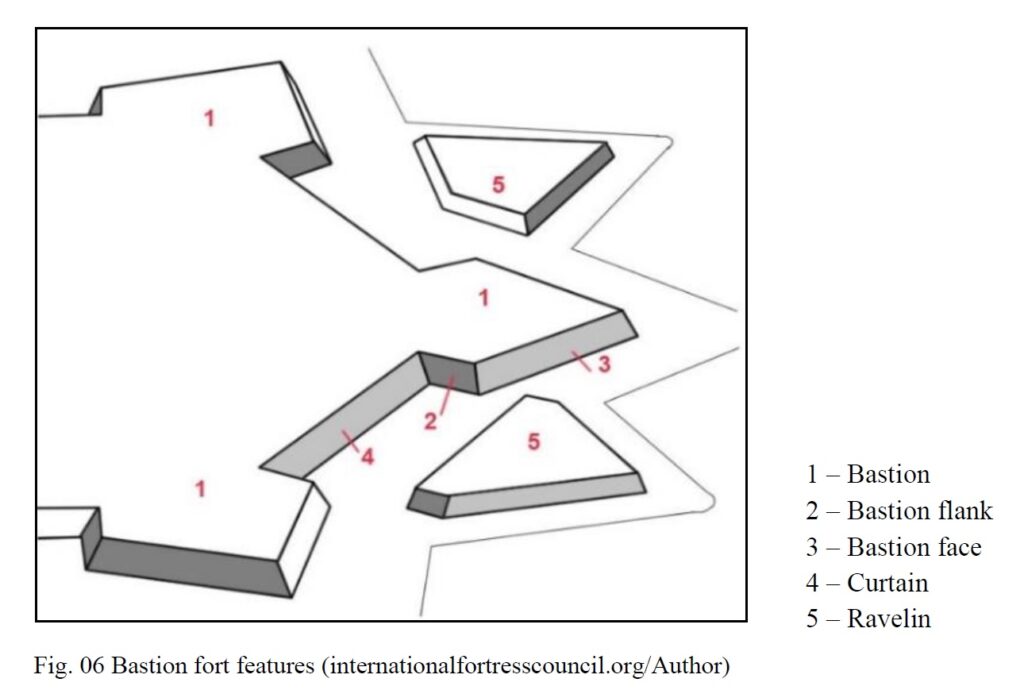

The resultant fort of this revolution mentioned above was commonly called the bastion fort, for the fact that the feature known as the bastion played an important role in the function of the fort. The bastion was designed in a geometric fashion with angles so that every point outside the fort could be covered by the guns of the fort. The bastion thus acted in a defensive function by covering the sides of the fort and as an offensive function by forming a battery that could counter enemy fire. The bastions were placed at the corners of the fort and joined by a curtain that formed the rampart. The fort was further protected by a moat which could be a dry or wet moat, and other outer features such as the ravelin, glacis, and hornwork.

The Italian system of fortification was commonly known as the trace italienne and was soon adopted by the Portuguese in their colonies during the 16th century. As such the Portuguese were the first to introduce the European system of fortification to Sri Lanka. The Dutch school of fortifications was further divided into the Old Dutch system or Oudnederlands Stelsel, the Improved Dutch and the New Dutch system, the latter was also known as the Coehoorn system after the pioneer engineer in the early 18th century. Figure 08. gives a simple overview of the three main schools of European fortress architecture and their variants.

The Old Dutch system was the first of the system of fortifications introduced to the colonies in the 17th century and is almost the exclusive type of fortress architecture of the Dutch forts of Sri Lanka. When the Dutch took over the Portuguese forts between 1638 and 1658, they most often rebuilt (sometimes integrating sections into their works) the Portuguese forts into their architecture as the former represented older designs of the trace italienne (see figure 08).

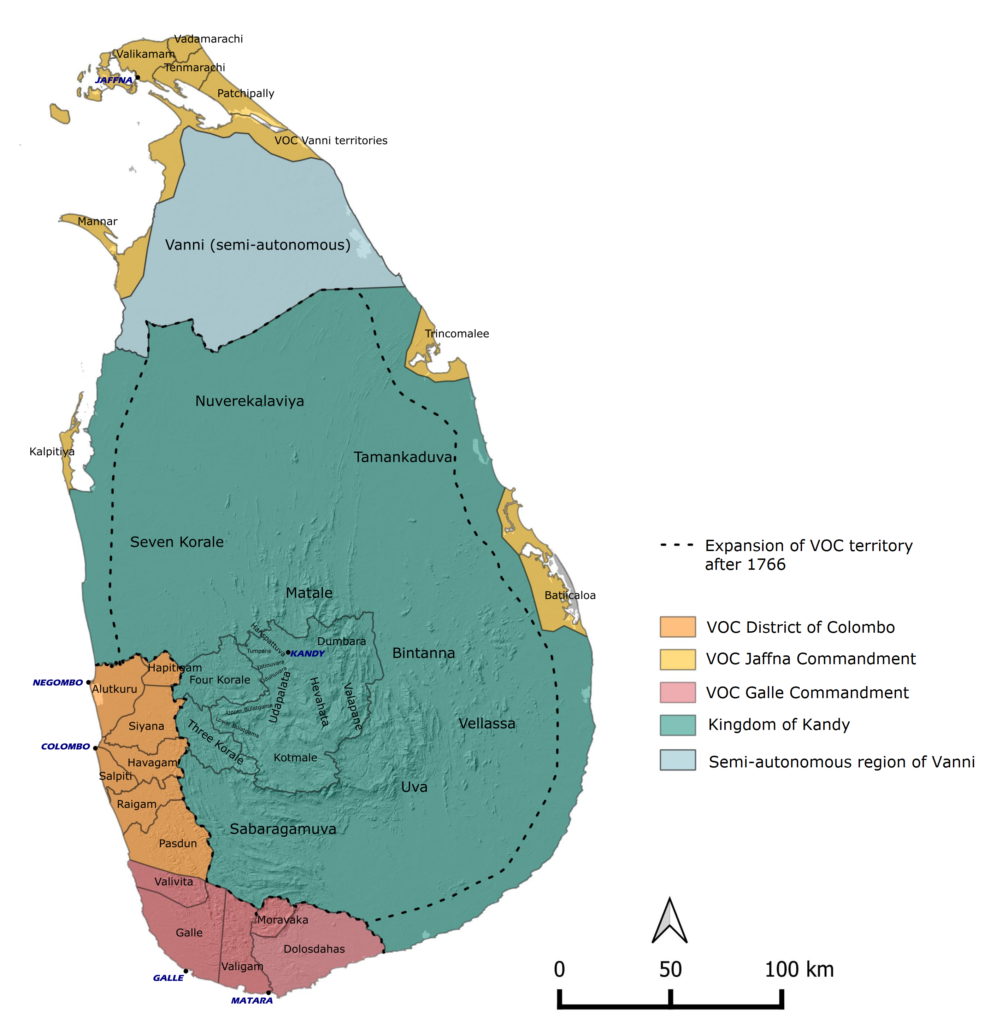

The VOC and their forts in Sri Lanka

Although the Dutch first arrived in Sri Lanka in 1602, it was only in 1638 that they entered into a treaty with the king of Kandy, which gave them a foothold in the island. In the initial years between 1638 and 1658 during the war with the Portuguese, they most often reused the Portuguese forts which were captured. However by the end of the 1650s they had begun to rebuilt the forts which they already occupied at that time according to their architectural standards. A characteristic of the Dutchman was his acute attention to planning and design, which is still seen in the Netherlands today. Therefore every fort and its internal layout was carefully planned out by qualified military engineers and surveyors.

The late 1650s and early 1660s were spent on consolidating their hold in the territories they occupied. This was primarily done through the redevelopment of the forts, some on the old Portuguese sites and some on new sites. Then the uneasy peace that existed between the Dutch and the kingdom of Kandy from the late 1650s came to an end when a rebellion broke out in the kingdom in 1664. King Rajasinghe requested the Dutch for assistance and one thing led to another and resulted in what could be aptly called the first Kandy-Dutch war between 1665 to 1675. (For full detail on this war see the link http://thehistoryfreek.blogspot.com/2021/04/first-kandy-dutch-war-1665-1675.html). This war saw an inland expansion of the Dutch territories which resulted in a large number of fortifications being built; the largest number of forts established during their entire period of occupation. However by the end of the 1600s the war was over and their governing policy and relations with Kandy had changed completely; therefore while all fortifications established during the war in Kandyan territory were abandoned, they even abandoned some posts within their own recognized territories.

Once again during the second Kandy-Dutch war between 1761 to 1766 (For full detail on this war see the link http://thehistoryfreek.blogspot.com/2021/04/second-kandy-dutch-war-1761-1766.html), they established more fortifications, some being at sites used and abandoned during the previous war. However towards the end of that century most forts were badly manned and soon fell to British hands, with only Trincomalee putting up a defence. Even the most well planned fort in the island, Jaffna, was abandoned in the face of the approaching British force.

Nature of the forts

For the Dutch like the Portuguese, the fort was everything. It functioned as a base of operations not only for military activities but for economic activities and administration as well. Such fortifications, whatever the size, were always located at strategic points, whether along the coast near ports or inland along main roads and rivers. The size of the forts depended on their function and not necessarily on their location, although in general, the larger forts are found along the coast near ports. The larger ones like Colombo and Galle were over 100,000 square meters while the smaller ones such as Arippu were around 450 square meters. Apart from what could be easily identified as a fort, there was another kind of fortification, one of more temporary nature and smaller than the smallest stone fort. Such sites mainly occur during times of war (during the two main wars with the kingdom of Kandy) and are variously termed such as guard-posts, out-posts, watch-posts, watch-houses, and stations. They tend to function for lines of communication (transport of letters), for garrisons of the local militia (Lascorins), for military campaign-related posts and campsites, or even as active defense works. Their form is not described, however, based on their smaller function, it could be interpreted that they were either a single building with some measure of defense or simple stockades.

The forts were designed to give complete protection to the Dutch establishment on the island, where they could function as part of a network of fortifications or as an independent unit. The enemies the Dutch kept in mind when designing the forts were the Kandyans and other European nations such as the English, French, and Danish. It could be also argued that based on the complexness of the larger defense works, the Dutch were mostly concerned with other Europeans rather than the local kingdom, whom they knew had not have the resources to siege such forts. Establishing forts also had another subtle function, apart from military, economic, and administrative functions; they were used to project ownership and authority of the lands.

When constructing the forts, the choice of primary material was generally selected on the availability of appropriate material in the area. While the core of the rampart was earth (dugout when cutting the moat), it was covered in a layer of solid material, which in Sri Lanka ranged from stone, coral, and kabook (laterite). Therefore the forts generally in the western coast were built of kabook, the northern ones out of coral and the southern ones out of stone. This however concerns only the larger forts or the ones used for a longer period. There were smaller forts built along the interior roads which were most often built of temporary material.

For a short case study description of the three forts of Colombo, Mannar, and Katuwana, follow the link http://thehistoryfreek.blogspot.com/2021/04/short-descriptions-dutch-forts-of.html

For short eye-witness accounts and other interesting snippets of the selected fortification sites of Anguruwatota, Arandara, Arippu, Arugambay, Bibilegama, Chilaw, Chundikulam, Gonavila, Iluppaikkadavai, Kananvila, Malwana, Puttalam, and Ratnapura, follow the link http://thehistoryfreek.blogspot.com/2021/04/short-insights-into-some-selected-dutch.html

The above is an attempt to give a brief overview of the nature of the forts built by the Dutch in Sri Lanka. A fort is a machine, with its fortifications being only one component of the machine. The garrison ÔÇô the soldiers, the cannon, the armory, etc. all form part of the machine that is the fort. Explaining these components is however left for another time.

Given below is a scientific classification of the form and function of the forts and also a chronological timeline. These are given here for the more curious reader. The list of sites and maps would follow this section.

Form and Function and classifications

Dr. Ranjith Jayasena is the first to systematically classify the fortifications of the Dutch in Sri Lanka. He puts forward a classification of the Dutch military posts in their functional and morphological aspects. In my thesis, I added one more classification type each for function and form.

| Main Forts | |

| Main forts – 1 | As major administrative, military and economic centers |

| Main forts – 2 | At strategic locations to safeguard the monopoly on trade goods |

| Main forts – 3 | As centers of storage of trade goods |

| Secondary Forts | |

| Secondary forts – 1 | To safeguard the trade monopoly and for the collection of the trade goods |

| Secondary forts – 2 | Primarily to defend the VOC territory |

| Secondary forts – 3 | Primarily to defend the VOC territory with the capacity for storage |

| Non-permanent watch-posts | Defense works that cannot be classified as forts but which were military in nature in overall defense and control of the landscape. |

Table. 01 Dutch forts classification based on function according to Jayasena (2010); last type according to Mendis (2020).

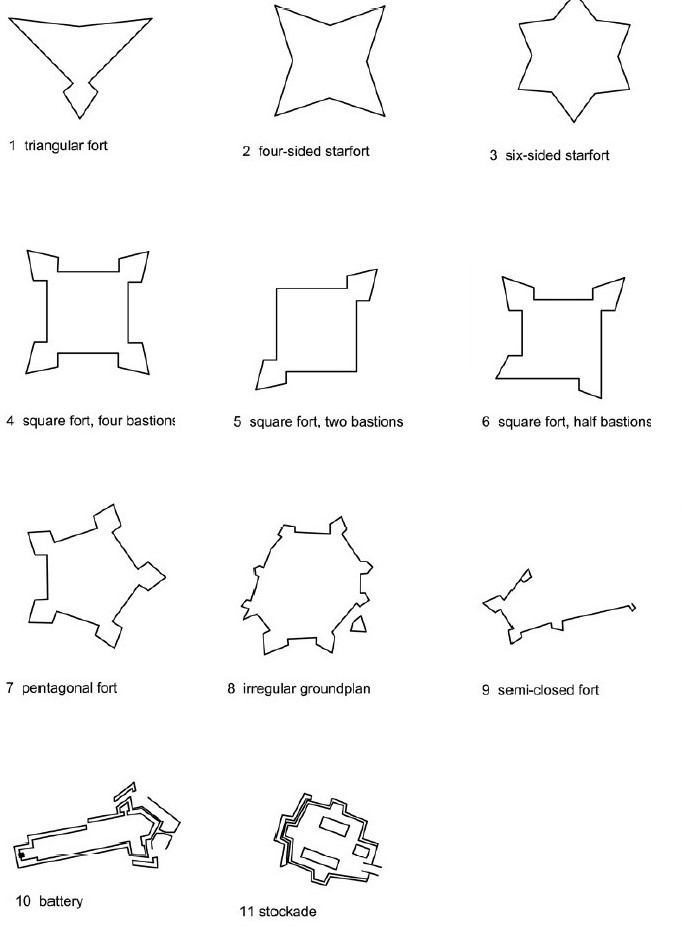

| Type 01 | Three-sided fort |

| Type 02 | Four-sided star fort |

| Type 03 | Six-sided star fort |

| Type 04 | Square fort with four bastions |

| Type 05 | Square fort with two diagonally opposite bastions |

| Type 06 | Square fort, a variant with half bastions |

| Type 07 | Five-sided fort |

| Type 08 | More-sided fort with a regular or irregular ground plan |

| Type 09 | Bastioned front, semi-closed fort |

| Type 10 | Battery (permanent) |

| Type 11 | Stockade (pagger), an earthwork with an irregular ground plan |

| Type 12 | Single building or stockade smaller than or less explicit to Type 11. |

Table. 02 Dutch forts morphological classification according to Jayasena (2010); last type according to Mendis (2020).

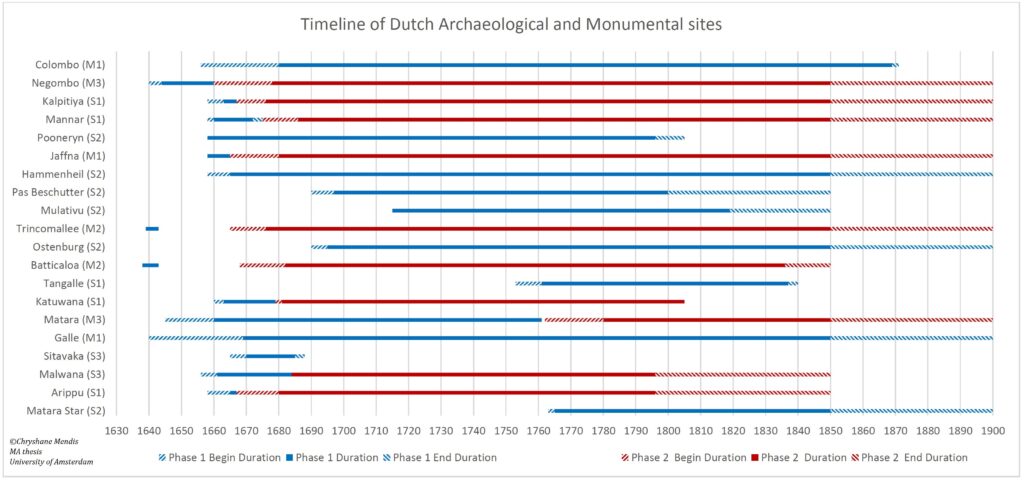

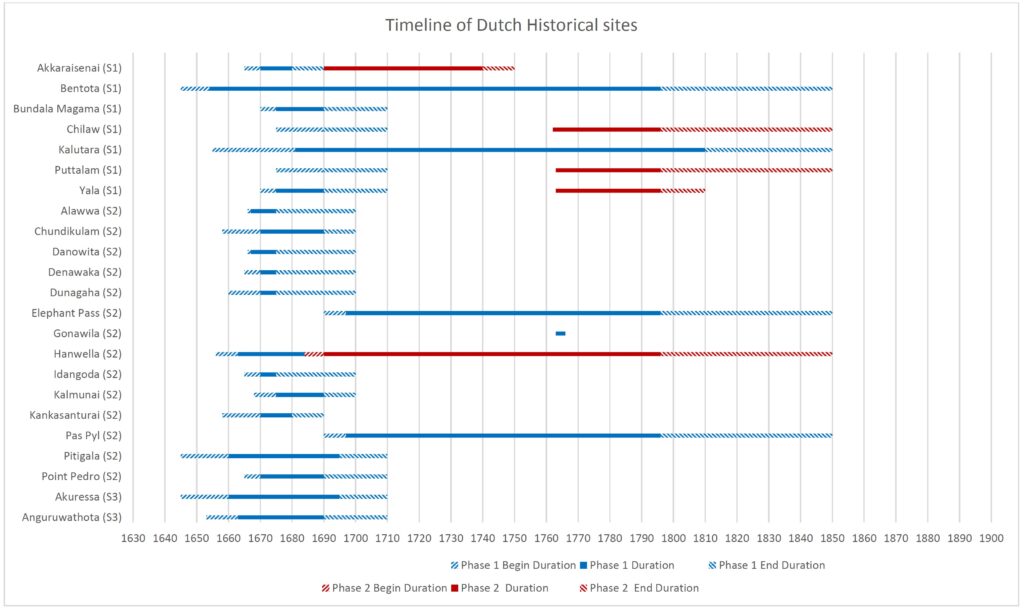

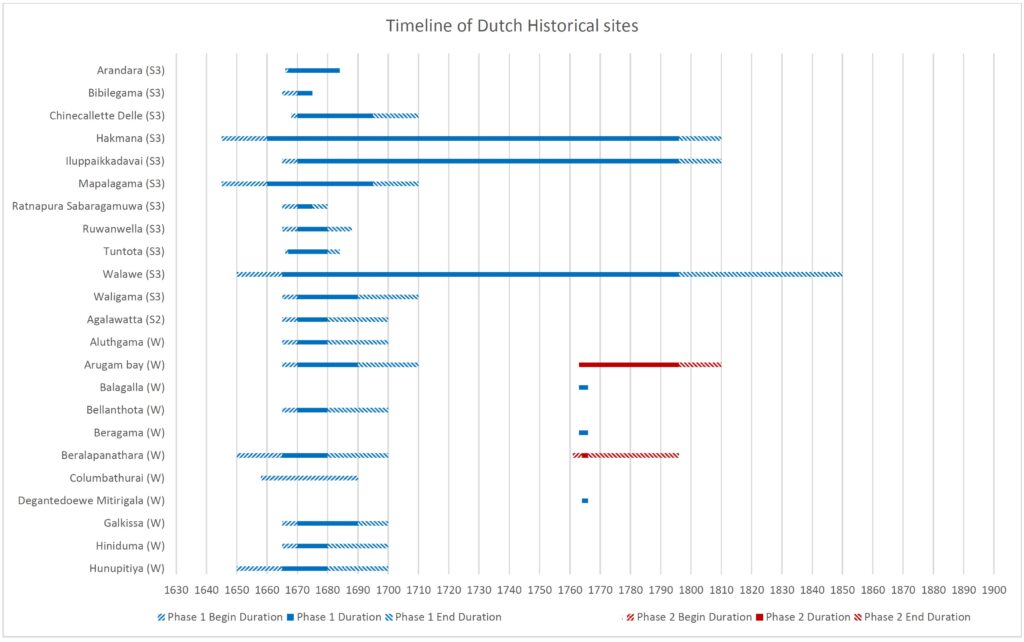

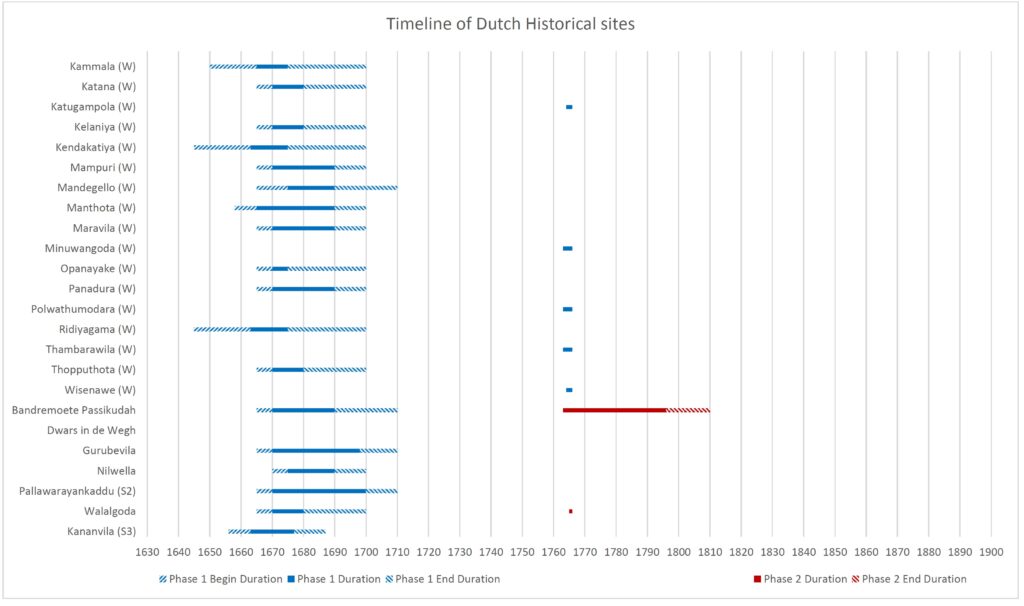

Timeline of sites

In my study, I defined the historical chronology as the beginning and end of use of the site for its intended function – as a fortification. ÔÇÿBeginningÔÇÖ here signifies the construction of the fort while ÔÇÿEndÔÇÖ signifies the abandonment, demolition or the end of its use as a fortification.

Obtaining exact dates was difficult and further in almost all cases of larger forts, they were constructed over several years or even decades. Hence a range of years was necessary to depict a siteÔÇÖs chronology. To this effect, a schema of earliest and latest dates was taken for the beginning and for the end.

| Beginning | Earliest date |

| Latest date | |

| End | Earliest date |

| Latest date |

Further, based on the historical survey of the fortifications, it was found that certain sites had the second phase of construction which was distinguishable from the first instance by form or chronology. Therefore the phases are distinguished as a) complete changes to the form in a continuous period (such as Katuvana from a stockade to the stone fort; Mannar from one form to the present form; Jaffna from the usage of Portuguese fort for a few years and reconstruction of new work), and b) abandonment and reoccupation after a long period of time/long interval ÔÇô several decades. Modifications to the existing form were not taken as a separate phase (e.g JaffnaÔÇÖs outer works from 1765-1792).

As the below graphical timeline would show, the forts were not static; that not all sites were begun, occupied, and ended at the same time. Some existed for a short period while others lasted longer, some had a second phase in a continuous period while other second phases occurred after a long interval. This temporal dimension can often be distorted in maps as it would only give a spatial overview.

Monumental and Archaeological sites

Through my thesis, I was able to identify twenty sites with remains at present. Eleven are complete monuments while nine are less complete (partial remains of internal structures, foundations, ramparts or gateways, etc).

Monumental sites

| Name | Function type | Form type | Historical territory | Present District | |

| 1 | Galle | M1 | 8 | Galle Kōralē | Galle |

| 2 | Jaffna | M1 | 7 | Valikamam | Jaffna |

| 3 | Trincomalee | M2 | 9 | Trincomalee | Trincomalee |

| 4 | Batticaloa | M2 | 4 | Batticaloa | Batticaloa |

| 5 | Mātara | M3 | 9 | Dolosdahas Kōralē | Mātara |

| 6 | Tangalle | S1 | 5 | Dolosdahas Kōralē | Hambantota |

| 7 | Kalpitiya | S1 | 6 | Kalpitiya | Puttalam |

| 8 | Mannar | S1 | 4 | Mannar | Mannar |

| 9 | Mātara star | S2 | 3 | Weligam Kōralē | Mātara |

| 10 | Hammenheil | S2 | 8 | Jaffna | |

| 11 | Katuvana | S3 | 5 | Dolosdahas Kōralē | Hambantota |

Sites with varying degrees of archaeological remains.

|   | Name | Function type | Form type | Historical territory | Present District |

| 1 | Colombo | M1 | 8 | Salpiti Kōralē | Colombo |

| 2 | Negombo | M3 | 7 | Aluthkuru Kōralē | Gampaha |

| 3 | Arippu | S1 | 5 | Mannar | Mannar |

| 4 | Pooneryn | S2 | 5 | Kilinochchi | |

| 5 | Pas Beschutter | S2 | 5 | Patchipally | Kilinochchi |

| 6 | Trincomalee Ostenburg | S2 | 10 | Trincomalee | Trincomalee |

| 7 | Mulativu | S2 | Mullaitivu | ||

| 8 | Malvāna | S3 | 6 | Siyana Kōralē | Gampaha |

| 9 | Sitāvaka | S3 | 4 | Three Kōralēs | Kegalle |

Historical sites

These are the sites documented in my thesis which lack any archaeological remains as per the data available to me during the time of writing. However, field surveys of these sites may still reveal surface features. Since the publication of my thesis, I was informed that the foundations of the Kalutara fort may still be there, even the foundations of the Hakmana fort. Therefore ground-truthing for such sites may reveal more traces.

These historical sites are further separated into the secondary forts and non-permanent watch posts (W) as classified above.

Historical Secondary forts

| Name | Function type | Form type | Historical territory | Present District | |

| 1 | Agalavatta | S2 | 12 | Pasdun Kōralē | Kalutara |

| 2 | Akkaraisenai | S1,S2 | 6,5 | Trincomalee | Trincomalee |

| 3 | Akurässa | S3 | 11 | Weligam Kōralē | Mātara |

| 4 | Alauva | S2 | 11 | Kurunegala | |

| 5 | Anguruvatota | S3 | 11 | Raigam Kōralē | Kalutara |

| 6 | Arandara | S3 | 4 | Four Kōralē | Kegalle |

| 7 | Bentota | S1 | 11 | Weliwita Kōralē | Galle |

| 8 | Bibil─ôgama | S3 | – | Ratnapura | |

| 9 | Būndala Māgama | S1 | 11 | Hambantota | |

| 10 | Chilaw | S1,S1 | – | Seven K┼ìral─ô | Puttalam |

| 11 | Chinecallette Delle | S3 | 4 | Batticaloa | Batticaloa |

| 12 | Chundikulam | S2 | – | Patchipally | Jaffna |

| 13 | Danōvita | S2 | 11 | Hapitigam Korlale | Gampaha |

| 14 | Denavaka | S2 | 11 | Ratnapura | |

| 15 | Dunagaha | S2 | 11 | Aluthkuru Kōralē | Gampaha |

| 16 | Elephant Pass | S2 | 5 | Patchipally | Kilinochchi |

| 17 | Gōnavila | S2 | 11 | Seven Kōralē | Kurunegala |

| 18 | Hakmana | S3 | 11 | Dolosdahas Kōralē | Mātara |

| 19 | Hanvälla | S2,S3 | 11,7 | Hewagam Kōralē | Colombo |

| 20 | Idangoda | S2 | 11 | Ratnapura | |

| 21 | Iluppaikkadavai | S3 | 5 | Mannar | |

| 22 | Kalmunai | S2 | 11 | Batticaloa | Ampara |

| 23 | Kalutara | S1 | 8 | Pasdun Kōralē | Kalutara |

| 24 | Kananvila | S3 | 4 | Raigam Kōralē | Kalutara |

| 25 | Kankasanturai | S2 | – | Valikamam | Jaffna |

| 26 | Mapalagama | S3 | 11 | Galle Kōralē | Galle |

| 27 | Pallavarayankaddu | S2 | – | Kilinochchi | |

| 28 | Pas Pyl | S2 | 5 | Patchipally | Jaffna |

| 29 | Pitigala | S2 | 2 | Weliwita Kōralē | Galle |

| 30 | Point Pedro | S2 | 1 | Vadamarachi | Jaffna |

| 31 | Puttalam | S1,S1 | -,4 | Seven Kōralē | Puttalam |

| 32 | Ratnapura | S3 | 5 | Ratnapura | |

| 33 | Ruvanvälla | S3 | 6 | Three Kōralē | Kegalle |

| 34 | Tuntota | S3 | 6 | Four Kōralē | Kegalle |

| 35 | Valavē | S3 | 11 | Dolosdahas Kōralē | Hambantota |

| 36 | V├ñligama | S3 | – | Weligam K┼ìral─ô | M─ütara |

| 37 | Y─üla | S1 | – | Hambantota |

Historical Non-permanent watch posts

| Name | Function type | Form type | Historical territory | Present District | |

| 1 | Alutgama | W | 12 | Weliwita Kōralē | Kalutara |

| 2 | Arugam bay | W | – | Ampara | |

| 3 | Balagalla | W | – | Aluthkuru K┼ìral─ô | Gampaha |

| 4 | Bellantota | W | 12 | Salpiti Kōralē | Colombo |

| 5 | Beragama | W | – | Hambantota | |

| 6 | Beralapanatara | W,W | 12,12 | Morawak Kōralē | Mātara |

| 7 | Columbaturai | W | 12 | Valikamam | Jaffna |

| 8 | Mitirigala | W | – | Siyana K┼ìral─ô | Gampaha |

| 9 | Galkissa | W | 12 | Salpiti Kōralē | Colombo |

| 10 | Hiniduma | W | 12 | Galle Kōralē | Galle |

| 11 | Hunupitiya | W | 12 | Aluthkuru Kōralē | Gampaha |

| 12 | Kammala | W | 12 | Seven Kōralē | Puttalam |

| 13 | Katāna | W | 12 | Aluthkuru Kōralē | Gampaha |

| 14 | Katugampola | W | – | Seven K┼ìral─ô | Kurunegala |

| 15 | Kälaniya | W | 12 | Siyana Kōralē | Gampaha |

| 16 | Kendakatiya | W | 12 | Dolosdahas Kōralē | Hambantota |

| 17 | M─ümpuri | W | 12 | Kalpitiya | Puttalam |

| 18 | Mandegello | W | – | Hambantota | |

| 19 | M─üntota | W | 12 | Mannar | Mannar |

| 20 | Māravila | W | 12 | Seven Kōralē | Puttalam |

| 21 | Minuvangoda | W | – | Aluthkuru K┼ìral─ô | Gampaha |

| 22 | Opan─üyaka | W | 12 | Ratnapura | |

| 23 | Pānadura | W | 12 | Raigam Kōralē | Kalutara |

| 24 | Polvatum┼ìdara | W | – | Weligam K┼ìral─ô | M─ütara |

| 25 | Ridiy─ügama | W | 12 | Hambantota | |

| 26 | Tambaravila | W | – | Seven K┼ìral─ô | Puttalam |

| 27 | Topputota | W | 12 | Seven Kōralē | Puttalam |

| 28 | Visen─üva | W | – | Seven K┼ìral─ô | Kurunegala |

| 29 | P─üssikudah | – | – | Batticaloa | Batticaloa |

| 30 | Dwars in de Wegh | – | – | Trincomalee | Trincomalee |

| 31 | Gurubevila | – | 11 | Hewagam K┼ìral─ô | Colombo |

| 32 | Nilvella | – | – | Dolosdahas K┼ìral─ô | M─ütara |

| 33 | Valalgoda | – | – | Ratnapura | |

| 34 | Beruwala | ||||

| 35 | Maggona |

[1] Jayasena, R. & Floore, P., 2010. Dutch forts of seventeenth-century Ceylon and Mauritius: An historical archaeological perspective. p.237

[2] Hughes, J. Q., 1974. Military architecture, p.102,134, 138