By Chryshane Mendis

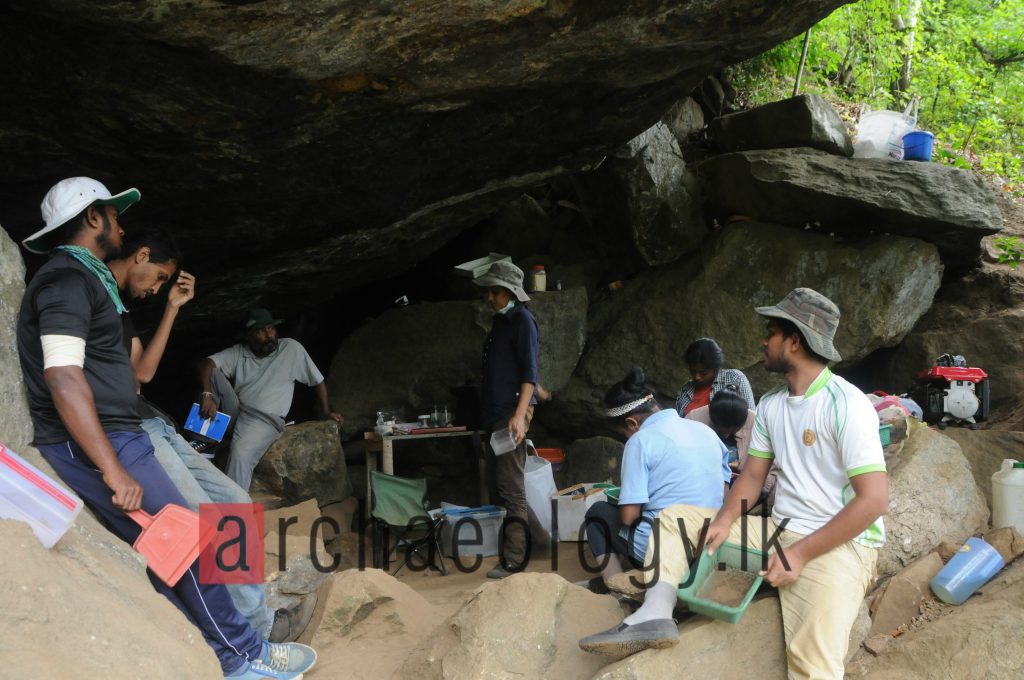

Excavation of the prehistoric site cave of Alugalge is conducted by the Field Archaeology Unit of the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology (PGIAR) led by Professor Raj Somadeva and a team of Researchers from the PGIAR and University students. The excavation which is funded by the PGIAR and the National Science Foundation (NSF) is part of the field work of the ÔÇÿHunters in TransitionÔÇÖ project which aims at identifying the pre and proto historic transition which would have occurred in the mid or late Holocene Epoch. This project is the extension of the research programme of ÔÇÿArchaeology of the UdaWalave BasinÔÇÖ begun in 2006 the area of which had been identified as an environmentally optimal area to study this transition. This 15 year project is currently running in its 9th season with the present excavation. The Archaeology.lk team visited the excavations in mid-March to gain an insight on this current excavation and as to what goes on during an archaeological dig.

Alugalge is located in the village of Illukumbura in Balangoda of the Rathnapura District. To reach here one must travel to Balangoda and upon reaching Kirimatithenna junction which is 3.5km passing Balangoda town on the Kaltota road, turn right on the Weligepola road and proceed about 10km to Kongasthenna junction. From here take the Illukkumbura road to the right and proceed about 5km passing the scenic Panana village to a sharp 90 degree turn to the left, from where one must take the small road to the right and travel about 2km through the hilly tea estates and home gardens to the Illukkumbura school and from here it is a 1km downhill hike from the road onto the left. The team of Archaeologists and Prof. Somadeva are based in a rented house in the beautiful peaceful village of Illukkumbura which is about 3km from the site.

[wpgmza id=”1″]

Alugalge Cave on Google Map

Summary of the excavations

Speaking to the Professor and the team, they explained that this is the second phase of the excavations of the prehistoric site of the Alugalge cave which commenced on the 20th February 2017 and is planned for a period of 6 weeks but that the duration could be extended or shortened based on the excavations.  This cave was for the first time surveyed and excavated in August 2016 which yielded evidence of prehistoric habitation and put the occupation of the site in about 3,450 B.C. with the most interesting find being that of a Shark tooth pendant.

Inquiring into the identification of this site, they explained that after every excavation an exhibition and awareness programme is conducted in the villages from which the residents share their knowledge of possible locations which are afterwards surveyed. The cave of Alugalge was one of the many such locations identified by the people and after conducting several surveys of other nearby caves, this particular cave was selected. Such programmes with the village folk have proved very valuable and their interest in identifying and reporting on possible locations is quite noteworthy and the help and support given to the excavation by people is remarkable as the writer witnessed.

Explaining on how they conducted the excavations; about a week was spent on surveying the site and only after a thorough survey is it decided to excavate. The cave, which was excavated on the previous occasion, was excavated to a further depth this season. Once the surveying was completed they laid the gird plan and conducted the profile drawing of the levels which is of most importance and only then was it begun to excavate.

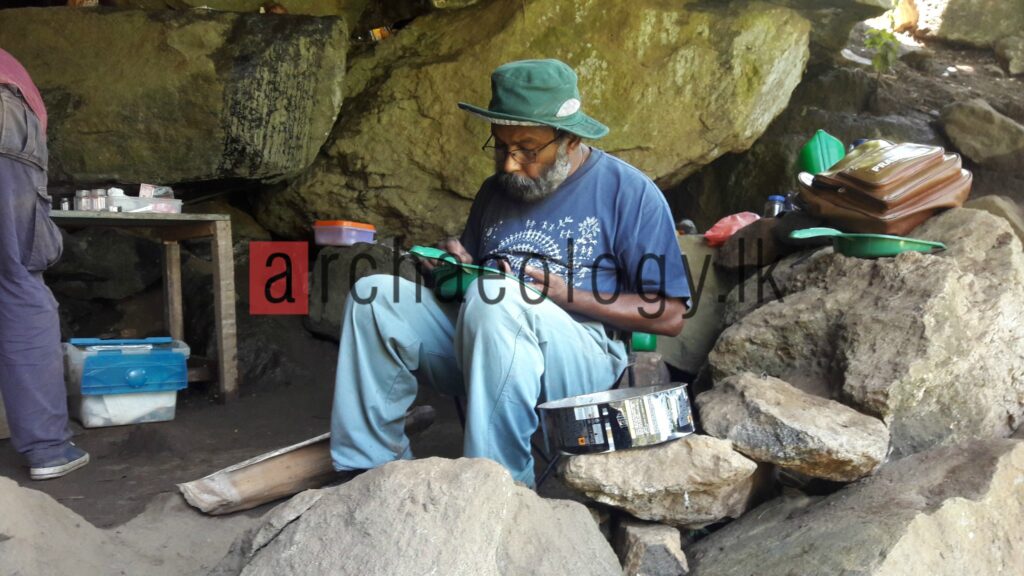

The excavated soil layers of excavations of the prehistoric site cave go through two processes in order to obtain artefacts, first by dry sieving and second by wet sieving. The section of the excavated soil is marked by the grid number and layer number for a systematic identification and only then taken through the above two processes which are conducted at the site. This dry and wet sieving is a careful process and is done through experienced hands due to the delicate nature of the artefacts. Artefacts are selected during these two stages as well and further after the wet sieving; the soil is carefully dried and brought in marked bags back to the house for a more careful piece by piece identification and selection.

The recovered soils which are carefully marked are brought back to the house and some entire days are spent on selecting the artefacts from them. When the writer visited the excavations, both days spent there were on this separation of artefacts from the soil layers; which as the writer witnessed is equally exciting and fun as digging in the cave because for to the archaeologically eyed participant, every step of an excavation be it in the field or indoors is sensational as something new to knowledge is brought to light every moment.

Once dried, the soil is spread on a white polythene sheet on a table and using a variety of twisers one by one the tiny particles are separated into different containers.

It is amazing as to the amount of artifacts that turn up from excavations of the prehistoric site cave just one bag of soil; for when spread out on the sheet, what seems like a heap of soil and dirt, when separated piece by piece reveals an array of artefacts. The artefacts found are Quartz stone tools and flakes, remains of animal bones and bone tools including teeth, shells, pieces of burnt clay, pieces of charcoal, and sometimes tiny pieces of graphite. The more remarkable findings are measured and cataloged separately for further analysis.

Stone tools are usually made from Quartz and Chert, but from this site only Quartz tools were found and make up the largest percentage of artefacts found and these are classified as microliths due to many being less than a centimeter in size.

Some of the shells discovered belong to the species Acavus haemastoma and seeds found here are identified as Dik Kekuna (Canerium zelanicum) which are still found in this area. These artifacts are then sealed in small transparent bags and labeled according to the grid and layer number from where they were excavated. These will be taken for further analysis.  The bags of soil recovered from the site amount to over a hundred and from morning till night are being painstakingly sorted out by the team. The patience that one requires to perform this is immense and it requires a trained eye to spot the artefacts from the soil and rocks.

When at the site the team would spend about 8 hours from 8 am in the morning till about 4 pm in the evening and when at the house as when the writer witnessed, from around 7 am they would sit on the benches sorting out the artefacts till 10 pm in the night only resting for meals and tea and the interesting stories of the Professor.

Traveling to the source of these wonderful finds, the Alugalge cave is located 3km from the house, the first two kilometers is motorable and turning off from the Illukkumbura school to the left we parked the motor cycle in a house nearby and began the 1km downhill hike to the cave. The first 500m is through the backyards of few houses and then takes a rather steep decent through patches of forests and small tea estates. The path is very narrow and there are many other footpaths joining the main path which makes it tricky but is now quite familiar to the team now used to trekking this path daily for almost a month. Traveling through the beautiful woods to a very low elevation the path turned north along a small ridge and came up beside a massive rock several dozen feet high, here lay the shelter of the prehistoric man, the Alugalge cave. The area has been arranged well for the dig, with a hose and tap brought from a nearby estate and much equipment such as spades and shovels including a generator used to light up the inside of the cave. The mouth of the cave opens up to the west and is surrounded by thick evergreen forests. When excavating, the team hikes down here daily, leaving the house at 7 am in the morning and arriving near the Illukkumbura School in a hired truck and making the downwards decent to the site carrying all the equipment and meals and work at the site till about 4 pm in the evening. The villagers are very supportive and have great respect to the Professor and team as the writer witnessed and many children from the village come to observe the excavations. For the lover of nature and history, this is the ultimate satisfaction.

The excavations of the prehistoric site are scheduled to conclude the end of March and only scientific analysis of the findings back at the PGIAR would reveal the full worth of this seasonÔÇÖs discoveries. The fascinating field of archaeology never fails to amuse the mind of even the most uninterested person with its wonderful stories of the past, spectacular findings, most of the time touched last by human hands over thousands of years ago and also the stories of the present, of the places visited, people encountered and the diversity of cultures witnessed. Although separated from family and friends for several weeks, the lover of archaeology is ever happy at heart for he who uncovers history finds happiness in diversity and wherever he or she may be, will always feel at home.

References

- Somadeva, R. (2011), Archaeology of the Uda Walave Basin. Occasional Paper no. 2, Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology, Colombo: Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology.

- Somadeva, R. (2014), Archaeology of Mountain, Occasional Paper no. 3, Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology, Colombo: Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology.

Sir im kasun from wattala st.anthonys college i would Like to ask you that is ravana real.

Dear Kasun,

In a simple answer, no, Ravana is not real. Why I say this is not because there are no archaeological evidence. We need to understand from where the ravana story comes from – the ramayanaya. And so we need to understand what the ramayanaya is. It is not a historical chronicle; it was written not as an account of history but for other purposes. It is similar to the book of Genesis in the Bible or the Epic of Gilgamesh. Such works were written as parables to teach morals and ethics. So thinking such stories were real is fundamentally wrong. It is like thinking the Lord of the Rings or Star Wars is real, no, they were written for the purpose of entertainment. We have approached the issue of Ravana in the wrong way by trying to say there is no archaeological evidence.