By A.M.A.Dayananda

* This article was first published in proceedings of ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL CONFERENCE ON UNDERWATER CULTURAL HERITAGE, 2011, Manila

Abstract

The shipwreck Earl of Shaftsbury is buried on the southern coast of Sri Lanka very close to a frequented tourist destination. It was run aground hitting on a rock at Akurala about three miles away from the shore. In 1893 when sailing from Bombay to Diamond Island the ship sailed past Rangoon through Colombo harbour after unloading charcoal. It is an iron build four mast sailing vessel. It collided with a reef due to rough waves. Six of the crew drowned and 22 survived. The shipwreck settled at a 50 foot depth. The incident was first reported in the The Ceylon Examiner Newspaper on 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th of May 1893. The value of the vessel was estimated at Indian Rupees (Rs.) 300,000 at the time. In one article there is another steamer ship reported wrecked some years previously. This paper includes details of the wreckage as are available from the newspaper reports. What happened after her wreckage was an interesting story. The time was the British colonial period in ÔÇ£CeylonÔÇØ (now Sri Lanka) during which time there was a growing general unrest against the colonial masters. Some information reveals that this mindset may have influenced the rescuers during their rescue efforts of the drowning crew. This paper it is going to elaborate on the story behind the shipwreck of the Earl of Shaftsbury and investigate the social influences towards the wreck site then and now.

Introduction

Even though Sri Lanka is a small island it is located at a geographically important juncture which joins the sea routes of East and West in the Indian Ocean. It was used as a trade centre within which goods were exchanged and as a resting place for navigators after a long sea voyage. ÔÇ£This ship was built in 1883 and belonged to the English firm The Browns and SonsÔÇØ(Bruzelius,1996). A metallic vessel with four masts and a contemporaneously superior ship on the company’s registration (The Ceylon Examiner Newspaper 08,05,1893). The ship had often arrived to the Colombo harbour but was wrecked in 1893 in the southern ocean of Sri Lanka marking its end of long sea voyages. The wreckage of the coal-transport ship is located between Hikkaduwa and Akurala and 14 meters deep in the seabed.

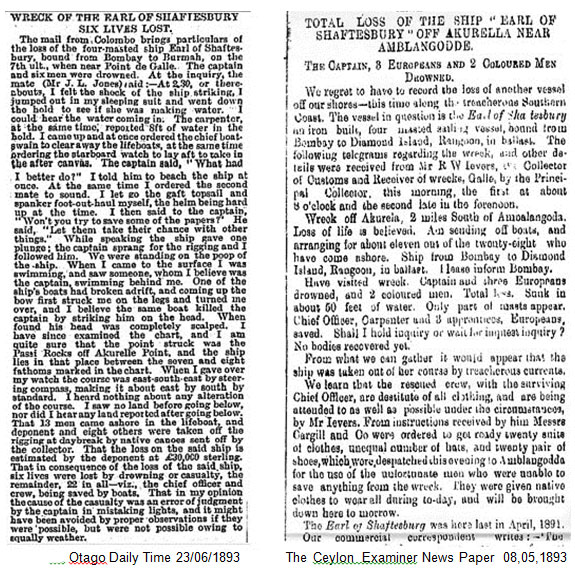

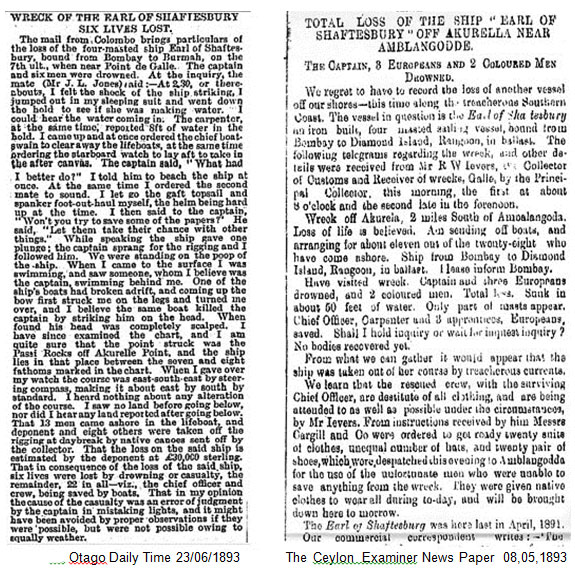

Two of the newspapers, The Otago Daily Times and The Ceylon Examiner (Figure 2) reported over several days of the ship’s tragedy and the problematic situation that the crew had to face after the wrecking. A minute detail of the reported facts and the way that they have been reported exposes the social background and the mentality of the social context.

Discovery and Recognition of the Ship ÔÇÿEarl of ShaftsburyÔÇÖ

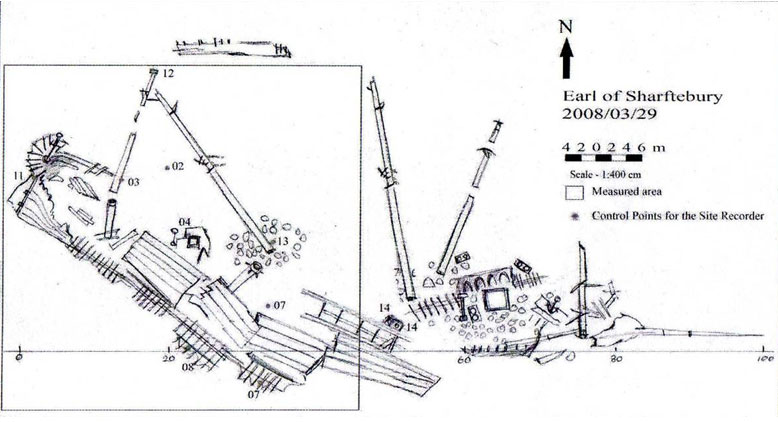

The Earl of Shaftsbury attracted both local and foreign divers visiting Hikkaduwa It was reported by Arthur C. Clerk in the 1960s.(Clerk 1956-57:p,38) A very brief introduction of it is also mentioned in his book The Reef of Taprobane.ÔÇØ We later discovered, marked the resting place of the Earl of Shaftesbury, which ran on to the Akurala Reef in 1893ÔÇØ (Clerk 1956-57:p,38). A formal survey on this place has not been done since the diving activities conducted in the 1960s. This shipwreck not only entails historic and archaeological value but bears great significance to bio diversity as well. The ship which provides a place of living for different marine species of various colours represents an important environmental system. The Maritime Archaeology Unit (MAU) in Galle, which is under the Central Cultural Fund, planned for an archaeological exploration on the shipwreck. Archaeological investigations on the ship first started in January 2008. The second step involved basic surveying activities in March and April 2008 by the participants of the Asian Pacific Regional Maritime Archaeology Training School established in association with the MAU (Figure 1).

[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

Scriptorium Research Work

Research was carried out on documents in search of the facts that had not yet been revealed. The divers who lived close to the site were aware that the Earl of Shaftsbury wrecked in 1893. The fact had been further proved by Clerk’s book The Reef of Taprobane. So steps were taken to carry out an archive search based on the year 1893. Nishantha Kumara, an undergraduate who came to the MAU as a volunteer was sent to search the old newspapers. The attempt was fruitful because the Examiner reported the details of the shipwreck. This ship had been built in the Leigh region in England by the firm Reimage and Ferguson. It was registered under Lloyds, the authority on certificates of quality for ships. The Earl of Shaftsbury was of the highest condition among the ships then registered under the firm(The Ceylon Examiner news paper 08,05,1893).

The length of the ship was 289.6 feet (ft.) and the width of it was 42.01 ft, her tonnage was 2079, and the dimension was 2869 ft. The owner of the ship was the Brown and Sons in England. The estimated value of the ship was three hundred thousand rupees in 1893. Out of the 28 members of staff on board, six lost their lives in the wreckage (The Ceylon Examiner Newspaper 08, 05,1893). The ship had sailed to Bombay from New York harbour in America loaded with paraffin oil and coal. The empty vessel, which had been reloaded with ballast stones for balance, wrecked while sailing around Sri Lanka towards Diamond Island in Rangoon. At the time of the wreck, the captain may have possessed a large sum of money; the money that the ship had earned from the goods unloaded at Bombay(Rasika,2010:p,06).

The Present Situation of the nautical ship, the Earl of Shaftsbury

According to the initial research carried out in 2008, it was observed that the central part of the naval ship had been severely damaged. Further investigations of the ruins revealed that this was not only natural causes but also due to the activities of treasure hunters and metal collectors, who had caused the destruction using explosives. The bow and the stern sections are still in good condition and the massive iron masts of the ship can be well recognized. The ballast stones that had been used to balance the empty vessel are still lying around the ship. The ship which lies inclining on its left maintains unity from the front to the back.

Field Strategies

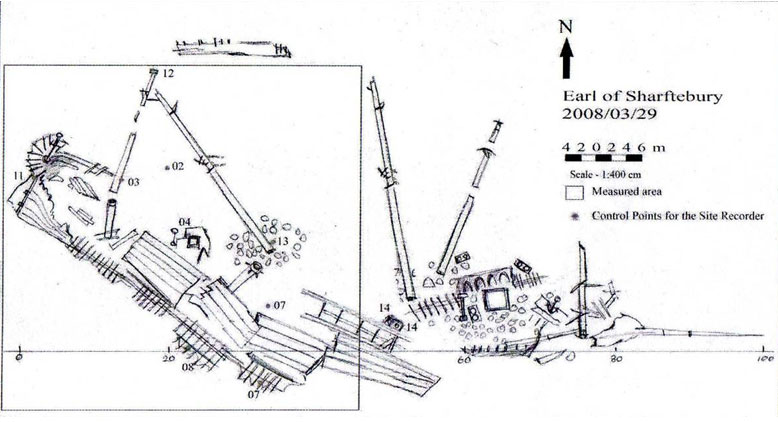

In 2008 the members of the MAU, did a survey on the wreck in a collaboration with the UNESCO Bangkok office. The wreck was measured and recorded by the team using 06 temporary control points fixed around the wreck. The site was divided in to two parts (from bow to mid-ship and from stern to mid-ship) and the two parts were measured separately. Each part was measured by using control points and the help of the Site Recorder program (a software developed by the 3H Consulting/United Kingdom). Also a base line was established covering the entire archaeological field. It was about 60 meters long and measurements were taken in the off-set method. For photographic records we used underwater digital still camera (Olympus C-770 camera with Ikelite housing) and video (Sony HC-90E camera with Ikelite housing). The expected goals were not achieved by this limited surveying activities conducted over four days(2008-03-27-29 and 2008-04-03) but they were enough to identify the naval ship as the Earl of Shaftsbury (Figure 4).

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

The Last Few Hours of the Earl of Shaftsbury

The ship sunk

due to natural hazards. The actual event was recorded by Leyers in (The Ceylon Examiner Newspaper 09,05,1893):

After cruising around Sri Lanka the ship sailed to the right of Colombo harbour towards the Diamond Island in the City of Rangoon. At about 3 a.m. the nature of the sea turned extremely wild and brought howling storms along. The ship was expeditiously glided forward and pushed up and down by the ferocious waves. Suddenly something black appeared before the crew who were observing the route in the front of the ship. Through intermittent flashes of lightening the crew identified a reef. At once the crew on board started shouting. As the captain rushed out of his cabin to examine the cry the ship collided on the rock with a big noise. The captain was overwrought by this and rushed into the control cabin in attempt to take the ship into the deep sea. His efforts were futile and the ship was repeatedly raised by the harsh waves and thumped several times against the rock. The ship was ultimately steered into the deep sea with the captain’s efforts. The ship had been unfortunately pierced by the knock against the rock and sea water rushed in. Soon it was filled with water and descending in the sea. Before the navigators stationed in the lower part of the ship’s decks had time to think the ship started sinking (The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09, 05,1893).

Some other navigators who were saved from drowning, said the captain watched the navigators fight for their lives against the harsh waves. The waves threw the crew about as they hung on to the masts that had emerged out of water and others clasped the wreckage of the ship. ÔÇ£The captain was spotted convulsing, entering his cabin and locking himself inÔÇØ(The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 10,05,1893) .Moreover, according to their revelations, at the moment of wrecking the Second Officer of the ship had acted immediately and been successful in launching a life saving boat. Fourteen navigators had boarded the lifeboat and headed towards the coast. The Earl of Shaftsbury then buckled up throwing all on board into the sea at about 150 meters from the coast. This unexpected incident made the tired crew more miserable (The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09,05,1893).

There were also recorded some inconsistencies with the events around the captain. This may be an indicator that the crew itself were largely unaffected by the death of the captain. Perhaps the first entry to follow is indicative of the locals’ mere dismissal of the captain, while the second entry is more emotional and perhaps more about the shocked tone of the crew.

The officers were housed by the special agent of the government until dawn and then taken to the guest house in Ambalangoda. Three days later the body of the captain, which had been badly destroyed, was carried to shore by the water. After recognition of the body by the chief officer of the ship and the rest of the crew, it was carried to Saint James church and buried with religious rituals (The Ceylon Examiner news paper,11,05,1893).

The Otago Daily Times (Allen 26,01,2010). revealed an entirely different story about the captain’s death,

according to Mr. Jones, a rescued crew member of the Earl of Shaftsbury, the only reason the captain died was because he fell off the lifeboat. The lifeboat had loosened in its ties from the ship and had fallen on the captain’s head while he was swimming for his life which knocked him out.

In the aftermath of the unfortunate event, (Levers,08,05,1893) records the reaction of the locals. This record is in fact a glimpse of the socio-politics at the time and is symptomatic of the Sri Lankan anger towards the European oppression.

The survivors had no other option but to swim for their lives. They swam a small distance and soon realized the European uniform they wore was a swimming hindrance. They pulled them off and swam towards the coast. They were reported to be mentally imbalanced and shocked, with bleeding wounds caused by being knocked against the rocks close-in to shore. The locals provided the naked navigators with native clothing. The surviving navigators later said that even though they requested the locals to save the lives of those who are still hanging on the masts and wreckage of the ship, they were denied with mentions that money was needed if they are to be saved. Later, all the men hanging onto the wreckage were saved by government special agents who were dispatched to the location. European suits were sent from Colombo for those officers who were clad in native clothes. The Examiner reported what a great shame for the Europeans to have been in native clothes for the whole day until the arrival of European uniforms(The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09,05,1893).

The Names of the Drowned

Captain T.B Mayyard, aged about 56 years,

Second Mate. W.K Loyle, aged about 20 years.

Steward, E. Morentz, aged about 21 years.

Sail Maker. W perry, aged about 50 year.

Two coloured seamen, natives of St Helena and Fiji Islands.

The Survivors

Chief Mate, JL Jones

Carpenter, W Guest.

Apprentices, G.O Trofaint, O.E pokely, and Thomson 14 coloured able seamen, 2 boatswains and the cook. Altogether 22. (The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09,05.1893).

Reported Incidents After Sinking; Lack of Humanity?

The Earl of Shaftsbury was smashed and wrecked in a period when Sri Lanka was a British colony (1815-1948). There had been no other shipwreck than the Earl of Shaftsbury to have revealed the detail of the area’s social background. The thoughts and ambitions of the locals who were ruled by the Europeans and some of their behaviours can be seen through these reports. ÔÇ£Humankind does not always continue to exist with the same monotonous life style. Their thoughts and ambitions do fluctuate with time. Exterior influences are mostly responsible for these fluctuationsÔÇØ(Somarathne 1960 p,01). When studying social impacts and noting the larger context in which people conduct themselves, projects like this one, can reveal an underlying agency. To address this, newspaper records of the navigators’ comments were gathered in hopes to note the voice of a colonized society. Among the reports that appeared on the wreckage the incident of not-saving crew members is the most highlighted fact. The Examiner reported that even though the surviving navigators had pleaded with the fishermen on shore to save the lives of the rest of the crew, the fishermen had demanded a considerable amount of money if they were to do so and would not otherwise. The newspaper report had highlighted that, ÔÇ£natives showed their lack of humanityÔÇØ (The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09,05,1893).

In my personal view, The behaviour of the fishermen at a crisis like this could never be appreciated and should not take place in any civilized society. Especially in a great society that has been nurtured by Buddhist philosophies. Yet the reason for such hard hearted people must be found out by a subtle and thorough case study. The people in that society were under true agony from being oppressed with revolutionary attitudes. The influence of three powerful European nationalities that largely focused on economic advantages, from 1505 AD fostered a feeling of loss of freedom and the consequential loss of their culture. Up to the time of the wreckage there had been no other opportunity to record the deep-seeded anti-colonial feelings. The fishermen, with the mentality for freedom, may have refused saving the navigators due to their revolutionary attitudes caused by this anti-colonial sentiment. They might have used this incident to show their frustration and envy towards the colonists. They might have thought they would have been betraying their own nation by rescuing their enemies. Furthermore they would have been reluctant to throw their lives at risk by launching their small boats when the sea had become so violent that even large ships, such as the Earl of Shaftsbury, were not safe.

The chagrin was not only visible in natives but also in Europeans. The report, ÔÇ£The Captain, Europeans and two Coloured men DrownedÔÇØ, ( The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 08, 05,1893). highlights this, in that the report on the survivors and the dead had grouped the black and Europeans separately. NavigatorsÔÇÖ were in local clothes until the European clothes were received and this was reported as an insult to them. All the above mentioned facts reveal that there had been a social conflict between the Europeans and the locals.

Conclusions

The only iron vessel with four masts so far found in Sri Lanka territorial waters is the wrecked Earl of Shaftsbury. This is an important research station for any marine archaeologist studying ship building technology. Although there are so many laws and conventions enacted internationally and locally in order to protect these monuments, there are many practical difficulties in implementing them. One of the main difficulties is to find funding for archaeological projects. We had to depend on funds allocated by the state under the national budget. So it has become a common feature for a developing nation like Sri Lanka to depend on funds from other sources. However, I emphasize that archaeological sites of this nature shall be further studied and shall be protected for the use of future generations. As a place of archaeological importance for more than 100 years this wreck site is protected by archaeological law (Department of Archaeology 1940; Department of Archaeology 1998). Besides, steps are been taken to declare this site as protective monuments under purview of Government of Sri Lanka and thereby will get a blanket coverage for the site.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the organizers of the Asia Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage for giving me an opportunity to participate. I also extended my gratitude to professor Mark Staniforth and professor Nimal de Silva, The Director General (Central Cultural fund) for encouraging me to publish this report.

Bibliography

| Allen, T.,2010 | “Wreck of the Earl of Shaftsbury six Lives Lost”, in Otago Daily Times 23 June Viewed 03 October 2011 http://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?138941/>. |

| Bruzelius, L.,1996 | Earl of Shaftesbury, Viewed 04 October , 2011.http://www.bruzelius.info/Nautica/Ships/Fourmast_ships/Earl_of_Shaftesbury(1883).html |

| Clerk, A.C.,1956-1957 | The reefs of Taprobane, printed in theunited states of America, Harper and Brother publishers,New York. |

| Departmentof Archaeology1940 | Antiquities ordinance No 9 |

| Departmentof Archaeology1998 | Amendment to the Antiquities ordinance No 9 of 1940 (21st May 1998) |

| Levers, R.W.,1893 | “Total Loss of The Ship Earl of Shaftsbury Off Akurella, Near Ambalangodde”, in The Ceylon Examiner News Paper, 08,09,10,11, May. |

| Rasika, M.,2010 | Dalanidu Magazine Vol II. Akurala verele Kedavachakaya Earl of Shaftsbury, Maritime Archaeology Unit Central cultural fund. |

| Somaratne, W.,1960 | A Modern Ceylon and world history,Ceylon publishing cooperation. |

By A.M.A.Dayananda

* This article was first published in proceedings of ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL CONFERENCE ON UNDERWATER CULTURAL HERITAGE, 2011, Manila

Abstract

The shipwreck Earl of Shaftsbury is buried on the southern coast of Sri Lanka very close to a frequented tourist destination. It was run aground hitting on a rock at Akurala about three miles away from the shore. In 1893 when sailing from Bombay to Diamond Island the ship sailed past Rangoon through Colombo harbour after unloading charcoal. It is an iron build four mast sailing vessel. It collided with a reef due to rough waves. Six of the crew drowned and 22 survived. The shipwreck settled at a 50 foot depth. The incident was first reported in the The Ceylon Examiner Newspaper on 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th of May 1893. The value of the vessel was estimated at Indian Rupees (Rs.) 300,000 at the time. In one article there is another steamer ship reported wrecked some years previously. This paper includes details of the wreckage as are available from the newspaper reports. What happened after her wreckage was an interesting story. The time was the British colonial period in ÔÇ£CeylonÔÇØ (now Sri Lanka) during which time there was a growing general unrest against the colonial masters. Some information reveals that this mindset may have influenced the rescuers during their rescue efforts of the drowning crew. This paper it is going to elaborate on the story behind the shipwreck of the Earl of Shaftsbury and investigate the social influences towards the wreck site then and now.

Introduction

Even though Sri Lanka is a small island it is located at a geographically important juncture which joins the sea routes of East and West in the Indian Ocean. It was used as a trade centre within which goods were exchanged and as a resting place for navigators after a long sea voyage. ÔÇ£This ship was built in 1883 and belonged to the English firm The Browns and SonsÔÇØ(Bruzelius,1996). A metallic vessel with four masts and a contemporaneously superior ship on the company’s registration (The Ceylon Examiner Newspaper 08,05,1893). The ship had often arrived to the Colombo harbour but was wrecked in 1893 in the southern ocean of Sri Lanka marking its end of long sea voyages. The wreckage of the coal-transport ship is located between Hikkaduwa and Akurala and 14 meters deep in the seabed.

Two of the newspapers, The Otago Daily Times and The Ceylon Examiner (Figure 2) reported over several days of the ship’s tragedy and the problematic situation that the crew had to face after the wrecking. A minute detail of the reported facts and the way that they have been reported exposes the social background and the mentality of the social context.

Discovery and Recognition of the Ship ÔÇÿEarl of ShaftsburyÔÇÖ

The Earl of Shaftsbury attracted both local and foreign divers visiting Hikkaduwa It was reported by Arthur C. Clerk in the 1960s.(Clerk 1956-57:p,38) A very brief introduction of it is also mentioned in his book The Reef of Taprobane.ÔÇØ We later discovered, marked the resting place of the Earl of Shaftesbury, which ran on to the Akurala Reef in 1893ÔÇØ (Clerk 1956-57:p,38). A formal survey on this place has not been done since the diving activities conducted in the 1960s. This shipwreck not only entails historic and archaeological value but bears great significance to bio diversity as well. The ship which provides a place of living for different marine species of various colours represents an important environmental system. The Maritime Archaeology Unit (MAU) in Galle, which is under the Central Cultural Fund, planned for an archaeological exploration on the shipwreck. Archaeological investigations on the ship first started in January 2008. The second step involved basic surveying activities in March and April 2008 by the participants of the Asian Pacific Regional Maritime Archaeology Training School established in association with the MAU (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The group that assisted the exploration (Photo – R. Muthucumarana)

Scriptorium Research Work

Research was carried out on documents in search of the facts that had not yet been revealed. The divers who lived close to the site were aware that the Earl of Shaftsbury wrecked in 1893. The fact had been further proved by Clerk’s book The Reef of Taprobane. So steps were taken to carry out an archive search based on the year 1893. Nishantha Kumara, an undergraduate who came to the MAU as a volunteer was sent to search the old newspapers. The attempt was fruitful because the Examiner reported cialis best price the details of the shipwreck. This ship had been built in the Leigh region in England by the firm Reimage and Ferguson. It was registered under Lloyds, the authority on certificates of quality for ships. The Earl of Shaftsbury was of the highest condition among the ships then registered under the firm(The Ceylon Examiner news paper 08,05,1893).

The length of the ship was 289.6 feet (ft.) and the width of it was 42.01 ft, her tonnage was 2079, and the dimension was 2869 ft. The owner of the ship was the Brown and Sons in England. The estimated value of the ship was three hundred thousand rupees in 1893. Out of the 28 members of staff onboard, six lost their lives in the wreckage (The Ceylon Examiner News paper 08, 05,1893). The ship had sailed to Bombay from New York harbour in America loaded with paraffin oil and coal. The empty vessel, which had been reloaded with ballast stones for balance, wrecked while sailing around Sri Lanka towards Diamond Island in Rangoon. At the time of the wreck the captain may have possessed a large sum of money; the money that the ship had earned from the goods unloaded at Bombay(Rasika,2010:p,06).

The Present Situation of the nautical ship, the Earl of Shaftsbury

According to the initial research carried out in 2008, it was observed that the central part of the naval ship had been severely damaged. Further investigations of the ruins revealed that this was not only natural causes but also due to the activities of treasure hunters and metal collectors, who had caused the destruction using explosives. The bow and the stern sections are still in good condition and the massive iron masts of the ship can be well recognized. The ballast stones that had been used to balance the empty vessel are still lying around the ship. The ship which lies inclining on its left maintains unity from the front to the back.

Field Strategies

In 2008 the members of the MAU, did a survey on the wreck in a collaboration with the UNESCO Bangkok office. The wreck was measured and recorded by the team using 06 temporary control points fixed around the wreck. The site was divided in to two parts (from bow to mid-ship and from stern to mid-ship) and the two parts were measured separately. Each part was measured by using control points and the help of the Site Recorder program (a software developed by the 3H Consulting/United Kingdom). Also a base line was established covering the entire archaeological field. It was about 60 meters long and measurements were taken in the off-set method. For photographic records we used underwater digital still camera (Olympus C-770 camera with Ikelite housing) and video (Sony HC-90E camera with Ikelite housing). The expected goals were not achieved by this limited surveying activities conducted over four days(2008-03-27-29 and 2008-04-03) but they were enough to identify the naval ship as the Earl of Shaftsbury (Figure 4).

The Last Few Hours of the Earl of Shaftsbury

The ship sunk due to natural hazards. The actual event was recorded by Leyers in (The Ceylon Examiner Newspaper 09,05,1893):

After cruising around Sri Lanka the ship sailed to the right of Colombo harbour towards the Diamond Island in the City of Rangoon. At about 3 a.m. the nature of the sea turned extremely wild and brought howling storms along. The ship was expeditiously glided forward and pushed up and down by the ferocious waves. Suddenly something black appeared before the crew who were observing the route in the front of the ship. Through intermittent flashes of lightening the crew identified a reef. At once the crew on board started shouting. As the captain rushed out of his cabin to examine the cry the ship collided on the rock with a big noise. The captain was overwrought by this and rushed into the control cabin in attempt to take the ship into the deep sea. His efforts were futile and the ship was repeatedly raised by the harsh waves and thumped several times against the rock. The ship was ultimately steered into the deep sea with the captain’s efforts. The ship had been unfortunately pierced by the knock against the rock and sea water rushed in. Soon it was filled with water and descending in the sea. Before the navigators stationed in the lower part of the ship’s decks had time to think the ship started sinking (The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09, 05,1893).

Some other navigators who were saved from drowning, said the captain watched the navigators fight for their lives against the harsh waves. The waves threw the crew about as they hung on to the masts that had emerged out of water and others clasped the wreckage of the ship. ÔÇ£The captain was spotted convulsing, entering his cabin and locking himself inÔÇØ(The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 10,05,1893) .Moreover, according to their revelations, at the moment of wrecking the Second Officer of the ship had acted immediately and been successful in launching a life saving boat. Fourteen navigators had boarded the lifeboat and headed towards the coast. The Earl of Shaftsbury then buckled up throwing all on board into the sea at about 150 meters from the coast. This unexpected incident made the tired crew more miserable (The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09,05,1893).

There were also recorded some inconsistencies with the events around the captain. This may be an indicator that the crew itself were largely unaffected by the death of the captain. Perhaps the first entry to follow is indicative of the locals’ mere dismissal of the captain, while the second entry is more emotional and perhaps more about the shocked tone of the crew.

The officers were housed by the special agent of the government until dawn and then taken to the guest house in Ambalangoda. Three days later the body of the captain, which had been badly destroyed, was carried to shore by the water. After recognition of the body by the chief officer of the ship and the rest of the crew, it was carried to Saint James church and buried with religious rituals (The Ceylon Examiner news paper,11,05,1893).

The Otago Daily Times (Allen 26,01,2010). revealed an entirely different story about the captain’s death,

according to Mr. Jones, a rescued crew member of the Earl of Shaftsbury, the only reason the captain died was because he fell off the lifeboat. The lifeboat had loosened in its ties

from the ship and had fallen on the captain’s head while he was swimming for his life which knocked him out.

In the aftermath of the unfortunate event, (Levers,08,05,1893) records the reaction of the locals. This record is in fact a glimpse of the socio-politics at the time and is symptomatic of the Sri Lankan anger towards the European oppression.

The survivors had no other option but to swim for their lives. They swam a small distance and soon realized the European uniform they wore was a swimming hindrance. They pulled them off and swam towards the coast. They were reported to be mentally imbalanced and shocked, with bleeding wounds caused by being knocked against the rocks close-in to shore. The locals provided the naked navigators with native clothing. The surviving navigators later said that even though they requested the locals to save the lives of those who are still hanging on the masts and wreckage of the ship, they were denied with mentions that money was needed if they are to be saved. Later, all the men hanging onto the wreckage were saved by government special agents who were dispatched to the location. European suits were sent from Colombo for those officers who were clad in native clothes. The Examiner reported what a great shame for the Europeans to have been in native clothes for the whole day until the arrival of European uniforms(The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09,05,1893).

The Names of the Drowned

Captain T.B Mayyard, aged about 56 years,

Second Mate. W.K Loyle, aged about 20 years.

Steward, E. Morentz, aged about 21 years.

Sail Maker. W perry, aged about 50 year.

Two coloured seamen, natives of St Helena and Fiji Islands.

The Survivors

Chief Mate, JL Jones

Carpenter, W Guest.

Apprentices, G.O Trofaint, O.E pokely, and Thomson 14 coloured able seamen, 2 boatswains and the cook. Altogether 22. (The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09,05.1893).

Reported Incidents After Sinking; Lack of Humanity?

The Earl of Shaftsbury was smashed and wrecked in a period when Sri Lanka was a British colony (1815-1948). There had been no other shipwreck than the Earl of Shaftsbury to have revealed the detail of the area’s social background. The thoughts and ambitions of the locals who were ruled by the Europeans and some of their behaviours can be seen through these reports. ÔÇ£Humankind does not always continue to exist with the same monotonous life style. Their thoughts and ambitions do fluctuate with time. Exterior influences are mostly responsible for these fluctuationsÔÇØ(Somarathne 1960 p,01). When studying social impacts and noting the larger context in which people conduct themselves, projects like this one, can reveal an underlying agency. To address this, newspaper records of the navigators’ comments were gathered in hopes to note the voice of a colonized society. Among the reports that appeared on the wreckage the incident of not-saving crew members is the most highlighted fact. The Examiner reported that even though the surviving navigators had pleaded with the fishermen on shore to save the lives of the rest of the crew, the fishermen had demanded a considerable amount of money if they were to do so and would not otherwise. The newspaper report had highlighted that, ÔÇ£natives showed their lack of humanityÔÇØ (The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 09,05,1893).

In my personal view, The behaviour of the fishermen at a crisis like this could never be appreciated and should not take place in any civilized society. Especially in a great society that has been nurtured by Buddhist philosophies. Yet the reason for such hard hearted people must be found out by a subtle and thorough case study. The people in that society were under true agony from being oppressed with revolutionary attitudes. The influence of three powerful European nationalities that largely focused on economic advantages, from 1505 AD fostered a feeling of loss of freedom and the consequential loss of their culture. Up to the time of the wreckage there had been no other opportunity to record the deep-seeded anti-colonial feelings. The fishermen, with the mentality for freedom, may have refused saving the navigators due to their revolutionary attitudes caused by this anti-colonial sentiment. They might have used this incident to show their frustration and envy towards the colonists. They might have thought they would have been betraying their own nation by rescuing their enemies. Furthermore they would have been reluctant to throw their lives at risk by launching their small boats when the sea had become so violent that even large ships, such as the Earl of Shaftsbury, were not safe.

The chagrin was not only visible in natives but also in Europeans. The report, ÔÇ£The Captain, Europeans and two Coloured men DrownedÔÇØ, ( The Ceylon Examiner News Paper 08, 05,1893). highlights this, in that the report on the survivors and the dead had grouped the black and Europeans separately. NavigatorsÔÇÖ were in local clothes until the European clothes were received and this was reported as an insult to them. All the above mentioned facts reveal that there had been a social conflict between the Europeans and the locals.

Conclusions

The only iron vessel with four masts so far found in Sri Lanka territorial waters is the wrecked Earl of Shaftsbury. This is an important research station for any marine archaeologist studying ship building technology. Although there are so many laws and conventions enacted internationally and locally in order to protect these monuments, there are many practical difficulties in implementing them. One of the main difficulties is to find funding for archaeological projects. We had to depend on funds allocated by the state under the national budget. So it has become a common feature for a developing nation like Sri Lanka to depend on funds from other sources. However, I emphasize that archaeological sites of this nature shall be further studied and shall be protected for the use of future generations. As a place of archaeological importance for more than 100 years this wreck site is protected by archaeological law (Department of Archaeology 1940; Department of Archaeology 1998). Besides, steps are been taken to declare this site as protective monuments under purview of Government of Sri Lanka and thereby will get a blanket coverage for the site.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the organizers of the Asia Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage for giving me an opportunity to participate. I also extended my gratitude to professor Mark Staniforth and professor Nimal de Silva, The Director General (Central Cultural fund) for encouraging me to publish this report.

Bibliography

| Allen, T.,2010 |

“Wreck of the Earl of Shaftsbury six Lives Lost”, in Otago Daily Times 23 June Viewed 03 October 2011 http://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?138941/>.

Bruzelius, L.,1996Earl of Shaftesbury, Viewed 04 October , 2011.http://www.bruzelius.info/Nautica/Ships/Fourmast_ships/Earl_of_Shaftesbury(1883).htmlClerk, A.C.,1956-1957The reefs of Taprobane, printed in theunited states of America, Harper and Brother publishers,New York.Departmentof Archaeology

1940

Antiquities ordinance No 9Departmentof Archaeology

1998

Amendment to the Antiquities ordinance No 9 of 1940 (21st May 1998)Levers, R.W.,1893″Total Loss of The Ship Earl of Shaftsbury Off Akurella, Near Ambalangodde”, in The Ceylon Examiner News Paper, 08,09,10,11, May.Rasika, M.,2010Dalanidu Magazine Vol II. Akurala verele Kedavachakaya Earl of Shaftsbury, Maritime Archaeology Unit Central cultural fund.Somaratne, W.,1960A Modern Ceylon and world history,Ceylon publishing cooperation.