Ivory craftsmanship

Sri Lanka has a rich history regarding many native traditional handcrafts. Among them, ivory craftsmanship has a special place. To study ivory craftsmanship and its technology in Sri Lanka we can use Sri Lankan literary and archeological sources. Especially according to early Brahmi inscriptions and archeological data, it’s important to understand the details of historical ivory craftsmanship in Sri Lanka. While looking into the traditional Ivory craftsmen and their artistry talents, we can see how ivory craftsmen stood among the early industrial handy crafts along with their marvelous and advanced craftsman techniques and ultimate utilization of limited materials.

Belong to the period around the third century B.C, ‘Wegiri devale’ first Brahmic rock inscription situated near the city of Kandy had the specific word ‘Datika’. According to Prof. Senerath Paranavithana, the meaning of Datika was ‘Ivory craftsman’.[i] Also, there is plenty of information from literary sources such as ‘wamsha katha’ which indicated that ivory craft has thrived as a craft even in ancient times. Even though ivory-crafted artifacts and information found belonged to the period of Kotte and Kandyan; there is no doubt that this craft started as a prehistoric craft and developed till the recent historical bias on the information from the Chronicle (wamsha kata)[ii]

There was information found in literary sources mentioned below to explore the early records of traditional ivory craft and its contribution to history.

King Dutugemunu donated an ivory-crafted chair and a ‘Wijithipathak’ (a palm-leaf fan used by a Buddhist monk) to the Buddhist monks whose residence at ‘Lowamahapaya’ has been recorded by Mahawamsa [iii]. During the period of king Jettathissa around 328- 337 A.D, ivory craftsmanship aspired as a craft[iv]. Especially, when the king himself being a professional ivory craftsman, indicated that it was a craft supported by the royalty. This showed how ivory craftsmanship was evolving throughout the Anuradapura period.

In the era of Polonnaruwa, king Parakramabahu – I built ivory-carved decorative pillars in bathing halls in ‘Nanadana Uyana’ (garden), mentioned in the second part of Mahawamsa (Chulawamsa).[v]. Not only that books like Saddarmarathnawaliya written in the 13th century A.D,  but Anagathawanshaya written during the 14th century A.D are also a few more literary sources must look into for more details. Also, by the time of the Kotte period the usage of ivory craft for decorating royal architects was popular according to information from messenger poetry (Sandesha Kavya)[vi]

There are much evidence of ivory craftsmanship found in archeological sources. The oldest ivory-crafted artifact founded during the excavation at the southern Wahalkada in Ruwanweliseya site in Anuradapura. It is a small female figure crafted on ivory. It was carbon dated to the second century B.C.[vii] Not only that, during the excavation conducted by Mr. Shanmugaum based on Magamtota in 1950, found a small ivory toy cart with excellent carvings on it[viii]

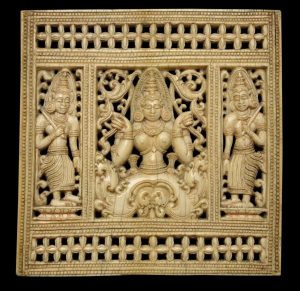

In the period of Sitawaka kingdom, a small scale crafted from ivory was one of the remaining marvelous specimens of ivory craftsmanship. Currently, it is to be found in the Colombo National Museum and it even had detailed carvings of liyapath motif (a leaf-like formation with a double curve) on the cover. This beautiful artifact dated back to the dynasty of king Seethawaka Rajasingha[ix] The Kandyan era has been recognized as the golden age of traditional Sri Lankan Ivory craftsmanship under the patronage of king Kirithi Sri Rajasinghe[x]. During that time, as the largest ivory piece in Sri Lankan history, the Kurunegala Ridi Vihara doorframe (Uluwasa) was created[xi]. It ‘Puncha Nari Gataya’ evidencing the beautiful and advanced artisanship during that time. Among the Sri Lankan ivory crafts, the statue of Lord Buddha was the main subject of many artists; especially, statues of sitting positions were popular. The biggest ivory carving of Lord Buddha was the one at Asigiriya Wijayasundararamay Raja Maha Viharaya in Kandy.

Based on archeological evidence and ethnoarchaeological studies from ancient times to recent history, Sri Lankan traditional Ivory crafts flourished with narratives of multi-purpose usage of ivory[xii]. Not only Ivory was used to showcase the essence of the craftsmanship itself but also to use to produce other practical applications and tools. Such as combs, daggers, windows, doors, heppu, styluses (Welipatha), knife handles, boxes, relic caskets, human figures, and betel mortar were created.

Because ivory was a sacred material, it is deemed to have a high demand for ivory-crafted items. Ivory, the tusk of an elephant itself was a prestigious symbol since ancient times. Because of these reasons, traditional ivory artisanship stayed prosperously during the British period and beyond in Sri Lanka. At the beginning of traditional ivory craftsmanship, which was passed down from generation to generation, lately maintained with high stranded as a handcraft industry[xiii]

Sri Lankan elephant tusks are recognized as premium quality ivory due to their thickness, quality, and appealing unique hue, even finding and using materials was difficult. By looking at the remains of carved tusk pieces, the technology and the talent of the artisans proved the value of the ivory craftsmanship was irreplaceable. A normal tusker’s tusk weighed around 50-60 pounds[xiv]. However, there are a few qualities that helped to choose these sacred materials as a medium to create marvelous pieces.

- Ability to achieve a shining finishing effortlessly

- The practicability of using tools in the marital

- The material itself had a high endurance to damages such as cracking, chipping under the climate/ meteorological conditions

- Long last without rusting or wearing off due to natural causes

- Being a scared material

Ivory craftsmanship was only practiced by the craftsmen who belonged to the master-craftsman caste. Master-craftsman caste was one of the social rankings during that time. It was also a social concept to keep alive the tradition of artistry. Master-craftsman caste had a wide range in its hierarchy. From high caste groups such as goldsmiths, and Ivory craftsmanship to inferior caste groups such as ironsmiths and painters. Especially regarding ivory craftsmanship, only craftsmen of a high rank were allowed in ivory carving while craftsmen (workers) from low caste were assigned in ivory turning. Depending on the work they do ivory carvers are known as ‘Ath-dath-kethaum-karuwa’ while the ivory turner is recognized as ‘Liyana waduwa’[xv]

To do the ivory turning a turning lathe was essential. It’s very similar to woodworking; turning ivory was not a complicated process. To this lathe; a router (liyana kañdha), two poles planted to the ground (known as Pita kanuwa and Wem kanuwa), a rope that rotates the router, and a stationary plane to rest the hand was needed. And tools like a drill, sews, rasp, and compass-like tool (adina kattuwa) were used. The elephant tusk needed to be turned it is to be connected to the outside of the axle of wem kanuwa. By doing this it is easy to empty the inside tray-like object (Heppuwa)[xvi]. Articles made with the lathe included fan handles, knife handles, implements and tools, scent sprayers, boxes, and horn fan handles. Most of the dots and circles cut by the lathe were decorated with a filling of colorful incisions. Dots were made with a sharp pointed tool while the circles were cut using a compass-like tool.Â

Cementum; the outer layer of the elephant tusk has a natural shine and a vibrant, which is a critical fact in choosing a suitable tusk for the ivory craft. It has a thickness of about 1/16,1/8 inches. But when a craving must be done, this outer layer needs to be removed. The part called dentine has many micro holes in it. These micro holes are filled with a natural mixture of substances. Ivory is suited for craving because of this soft unique wax-like substance. Even when time passed and if this waxy surface dried causing cracks, it will not affect the shine or the beauty of the tusk at all. Unlikely like a metal surface, the tusk surface will not face any troubles like wearing out or the surface getting rough. However, the talent and the skillfulness of ivory artists had brought up ivory craftsmanship magnificently throughout history[xvii]Â

Another interesting point regarding the traditional ivory craft in Sri Lanka is the beautiful decorative elements such as motifs from old Sinhalese painting handcraft that have been used. Also, the secret methods the craftsmen carried through many generations could be seen used in this process. Designs like Bherunda pakshiya, Hansa puttuwa, pala pethi, Kisibi muhuna, the figure of the dragon (Makara), lotus flower, Thirigithalaya, kundirikan, arinbuwa were a few of the most used designs[xviii]. When categorizing the motifs and designs used in ivory crafts there are few ways to dosuch. Among them, figure designs of animal, human, divine, and floral motifs were eye-catching. Â

Because of the difficulty of getting elephant tusk and being a limited material, it is considered a prestigious act to have ivory-crafted items in one’s procession. Since ancient times kings, ministers, and nobles have used ivory-crafted items due to that belief. Also, ivory crafts have caught the attention as merchandised goods by the foreign merchants who were on good terms with Sri Lanka considering international trading. Especially after the 15th century BC, there was a wide recognition for Sri Lankan ivory and ivory crafts in the Europe market. According to a foreign literature source, ‘Periplus Maris Erythraei’ ivory was exported to China during the year of 97 A.D.[xix]

Also, there is much evidence that proved ivory crafts were gifted to foreign diplomats and officials in historical times. Â

Today the traditional ivory craftsmanship which once flourished in Sri Lanka seems to have reached its end. Considering the information gathered through the research, it is clear that traditional ivory craftsmanship was in an excellent state until the recent historical time in Sri Lanka. But at present, it is even impossible to find tuskers or any ivory. However, there is no doubt that this great craft and its artisanship would be limited in the future.

[i] Senarath Paranavitana (1970), “ Vegiriya – Devala Inscriptionâ€, Inscriptions of Ceylon, Volume I, Early Brahmi Inscriptions, Department of Archaeology, Ceylon. 62p. No. 807.

[ii] Mahavansaya, (Sinhala) tr. Buddhist Cultural Center, Colombo, 2003, 113p.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid, 160p.

[v] Ibid, 392 p.

[vi] Ranjith Hewage (2012), “Seethawaka Rajasinghe Rajuta Ayath Ath Dala Tharadiya†(Sinhala Article), Vismitha Atheetha Urumayan, Susara Publication.18p.

[vii] H.W. Kumarathunga (2002), “Madyakaleena Mahanuwara Yugaye Paramparika Kala Karmantha†(Sinhala Article), ‘Chithra Kalawa’, S. Godage & Brothers Publications.34p.

[viii] https://roar.media/sinhala/main/health-lifestyle/artof-ivory-carving

[ix] Ranjith Hewage, Ibid. 21p.

[x] Ananda Coomaraswamy (1986), Mediaeval Sinhalese Art, Ministry of Cultural Affairs, Colombo, 185p.

[xi] Sanath Dharmabandu (2011), “Sri Lankawe Kala Karmantha†Chithra Ha Murthi Kalawa (Sinhala), M.D. Gunasena & Company. 55p.

[xii] Chulani Rambukwella, (2016), “Traditional Ivory Crafts and Technology in Sri Lanka: A Historical and Technological Perspective†In: International Conference on Asian Elephants in Culture & Nature, 20th – 21st August 2016, Anura Manatunga, K.A.T. Chamara, Thilina Wickramaarachchi and Harini Navoda de Zoysa (Eds.), (Abstract) p 164, Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. 180 pp. ISBN 978-955-4563-85-8

[xiii] H.W. Kumarathunga, Ibid. 38p.

[xiv] Ananda Coomaraswamy, Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Chulani Rambukwella, Ibid.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] https://roar.media/sinhala/main/health-lifestyle/artof-ivory-carving

[xix] G.H. Lesli Gamini (2016) Ancient Trade In Sri Lanka (Sinhala), Sooriya Publishers, Colombo. 98p.